By Tom Modugno of Goleta History

Isla Vista. The mere mention of the name brings a flood of emotions, opinions and memories to a local. A lot has happened on this small area of land in a short amount of years.

When you cram thousands of people into less than two square miles, you can expect a lot of stuff to happen. Especially when the majority of them are young and…..vibrant. Major businesses and big name bands got their start here, riots brought worldwide attention, and the parties are notorious. But why did our leaders decide to put all this housing in one little area? How did this happen? What was there before? Let’s get to the answers before those apartment buildings fall into the ocean!

The earliest known name for Isla Vista is ‘Anisq’oyo, which means “at the Manzanita”. This name is confusing because the manzanita tree that is native to this region grows only in higher elevations. Perhaps there was a structure made of manzanita or some other manzanita related event that occurred in this area. For whatever reason, the name lives on today as a park in the middle of Isla Vista. Surprisingly, one of the most densely populated areas in California today had no Chumash villages in it, most likely due to the lack of fresh water.

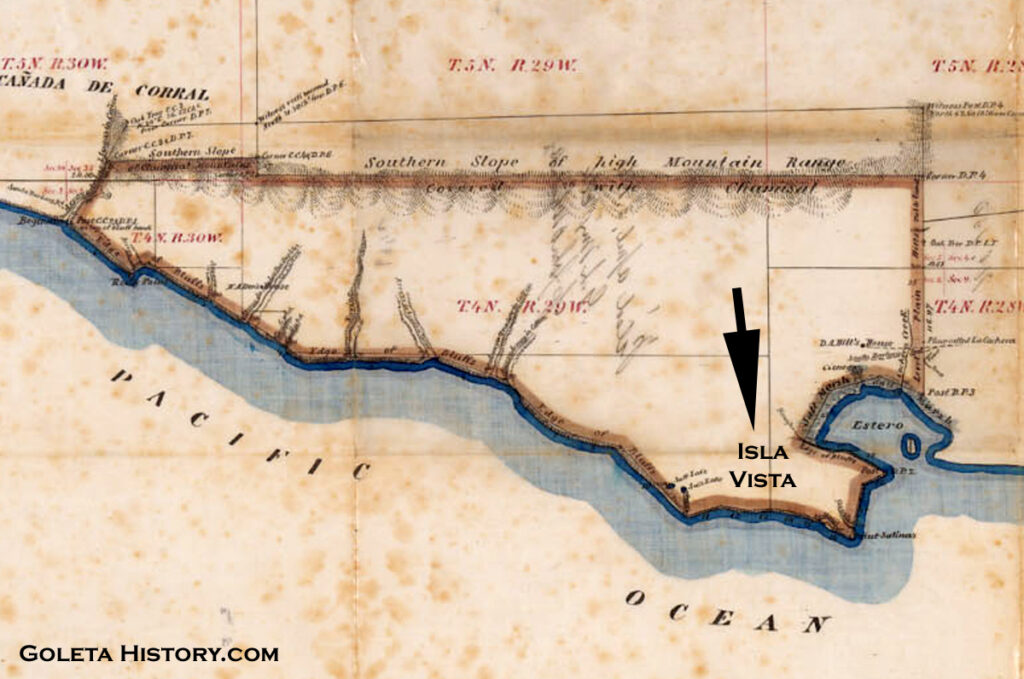

In 1842, Nicolas Den was awarded the 15,500 acre Dos Pueblos land grant that extended from today’s Goleta Slough to just east of El Capitan. Den’s massive ranch included the Isla Vista mesa, but he never made much use of this area since he was a cattle rancher, and this area was covered by a dense oak grove that made grazing impossible.

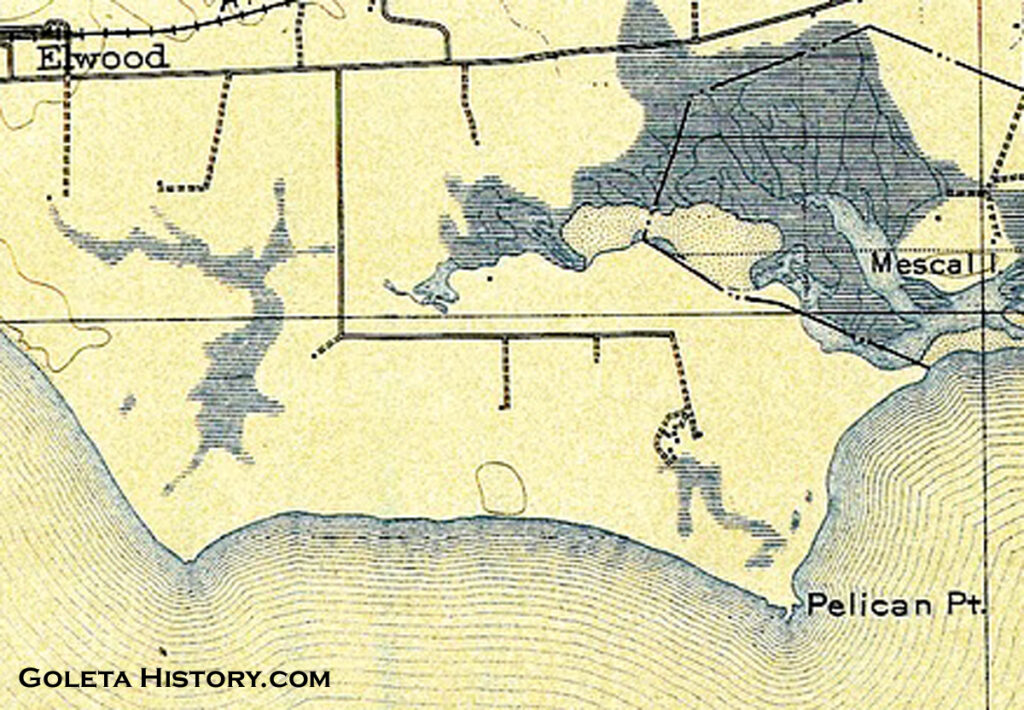

The Den family called the area from Coal Oil Point to Campus Point the “Rincon Ranch”. Rincon means corner in Spanish, and this was in reference to the sharp right angle turn on the old ranch road, shown above. Today that sharp turn is the corner of Storke and El Colegio Roads. (Also notice Campus Point is labeled as Pelican Point, one of many short-lived names for today’s favorite surf spot.)

When Nicolas Den passed away in 1862, he left half of the ranch to his wife and the other half to his ten children. Within a couple of years, several extreme weather events brought hard financial times to most California ranchers, including the Dos Pueblos Ranch. The Den family lawyer Charles E. Huse, pictured, was tasked with finding ways to keep the Dens out of bankruptcy. He took to the job with reckless abandon, often not bothering to check with the family before he took action. Ranch assets were sold and eventually large chunks of the Dos Pueblos Ranch real estate were being sold off to raise money.

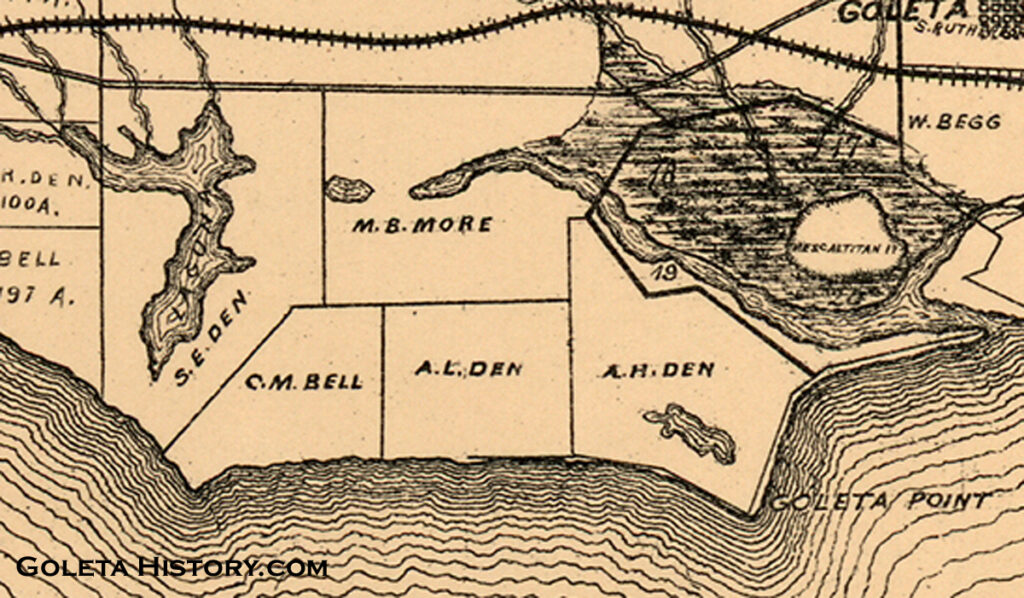

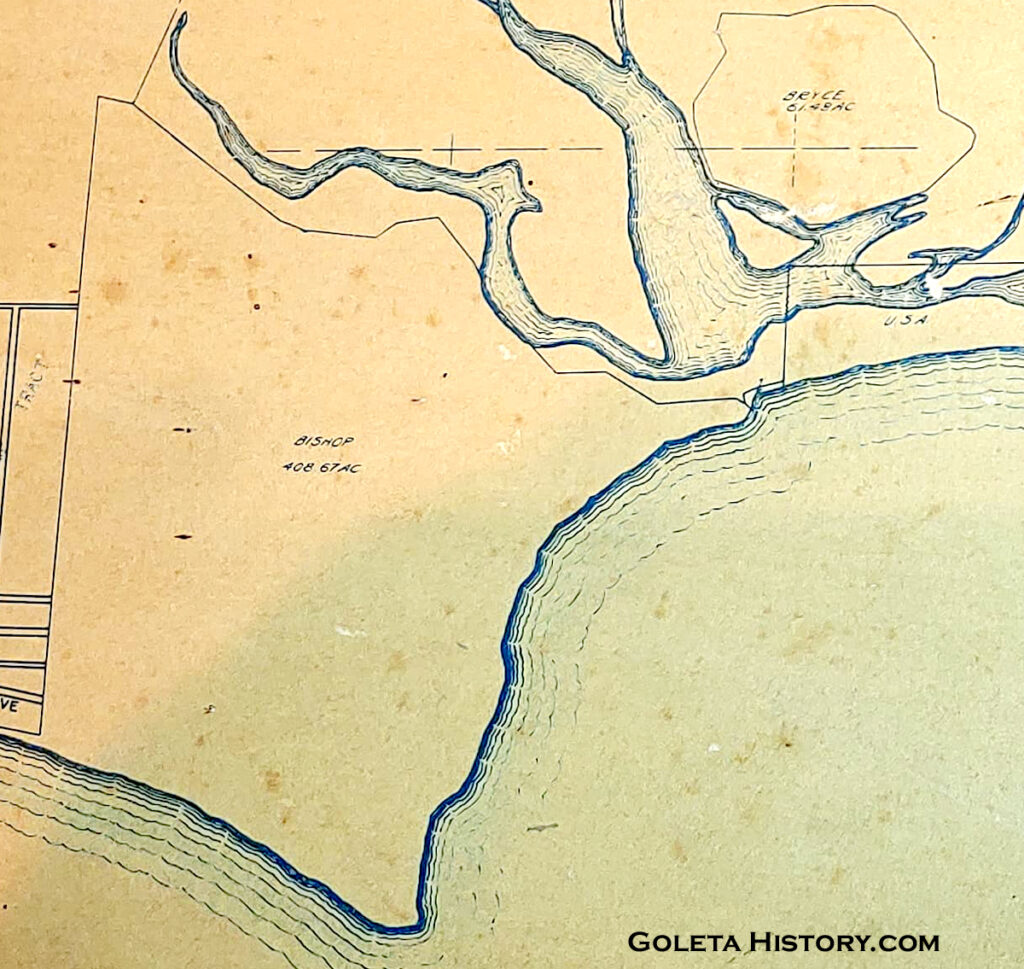

The Rincon Ranch area was split between three of the Den siblings, Catarina Den Bell, Alfonso Den and Augusto Den. Without a quality water source, the land was nearly worthless, despite the primo oceanfront location and the beautiful mountain views. There were a few 20 foot wells that produced a small amount of water, maybe enough to grow some hay or beans, but that was about it. They planted eucalyptus trees on the dividing lines of their parcels, many of which are still there today. The line between Alfonso and Augustus Den’s properties is today often called the Eucalyptus Curtain between UCSB and Isla Vista.

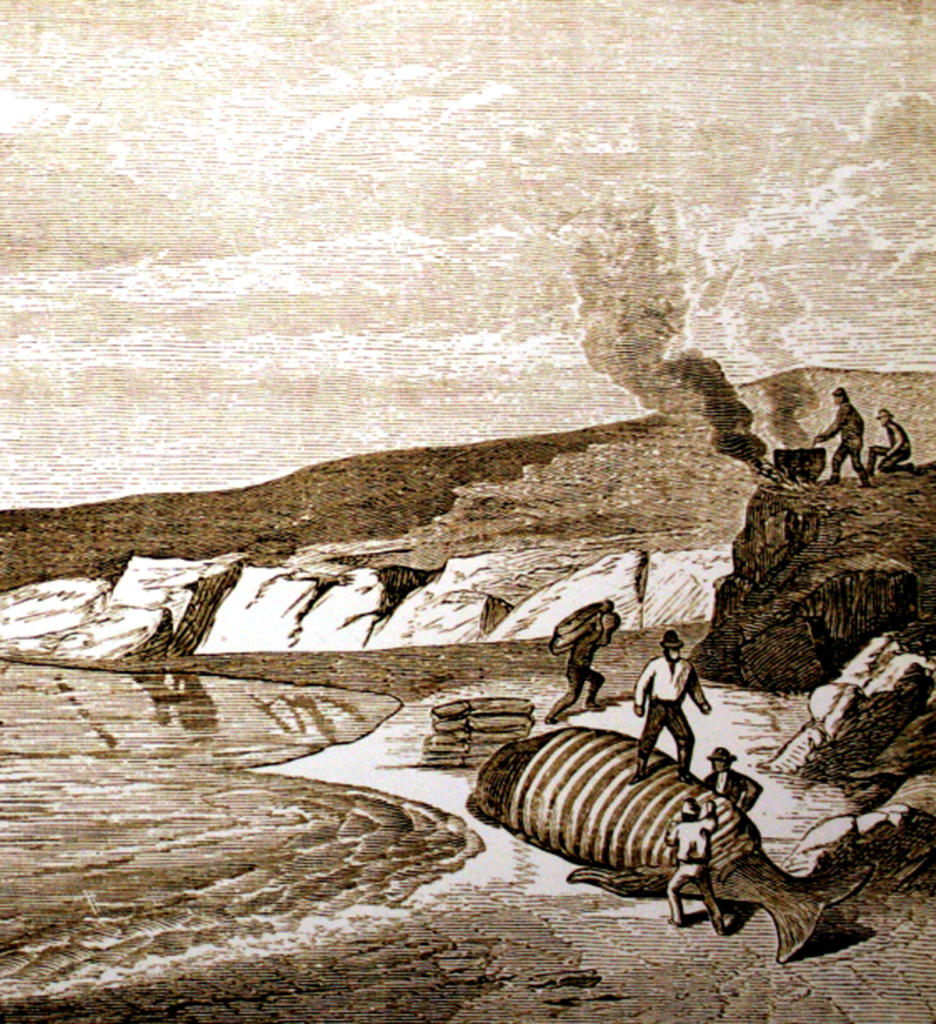

Charles Huse found a way to make part of the Rincon Ranch temporarily profitable. In the 1870s, he leased part of it to the More brothers and they proceeded to clear cut the live oak forest that grew there for sale as fire wood. They had an eager customer right next door at the Goleta Beach whaling stationthat needed fuel to melt down the whale blubber. Over 1,000 cords of oak wood were cut and sold without the permission of the Den family, and they received none of the proceeds from the sales!

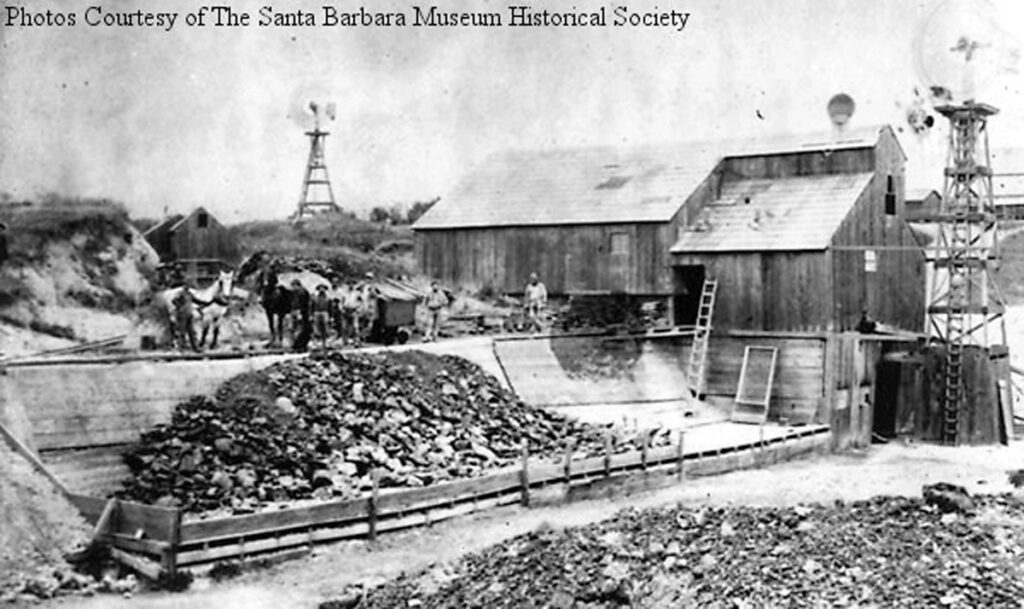

In 1890, the asphalt industry came to Goleta, and the most lucrative mine landed right in the lap of Augusto Den. The Alcatraz Asphalt Company leased part of the land that the More brothers had clear cut, and they started pulling 60 tons of asphalt out of the ground every 24 hours. What had long been considered the most worthless part of the Den family empire made “Gus” Den a wealthy man. Today this would be on the UCSB campus.

After the asphalt mine closed, the Dens had a treeless, waterless piece of real estate that they didn’t have a lot of value. In 1915, Alfonso Den sold a portion of his property to John and Pauline Ilharreguy from Fillmore. They had a grand scheme for this scenic, but seemingly worthless, piece of oceanfront property. The Ilharreguys paid $100 in gold for 157 acres of barren windswept land on the bluff above the ocean and went to work planning a coastal community that had a gimmick.

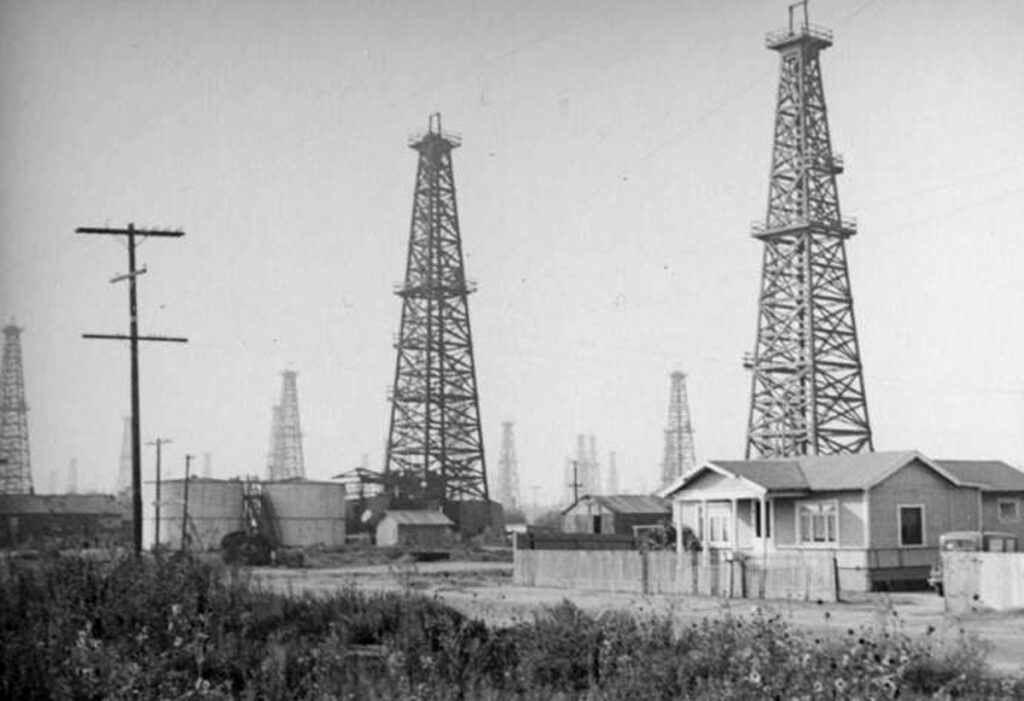

In 1910, the state of California produced 77 million barrels of oil. While we don’t know much about the Ilharreguys history, we can assume they knew this fact. They surely also knew that the mesa they were about to buy was right between a former asphalt mine and Coal Oil Point, that was covered with tar.

In 1923, Gus Den put his parcel (that had the asphalt mine on it) up for sale with an option to drill for oil first. After one potential buyer opted out we can assume he found no accessible oil. The Bishop Ranch ended up buying the land to expand their already massive operation. But the fact that no oil was found there didn’t discourage the plans of the Ilharreguys.

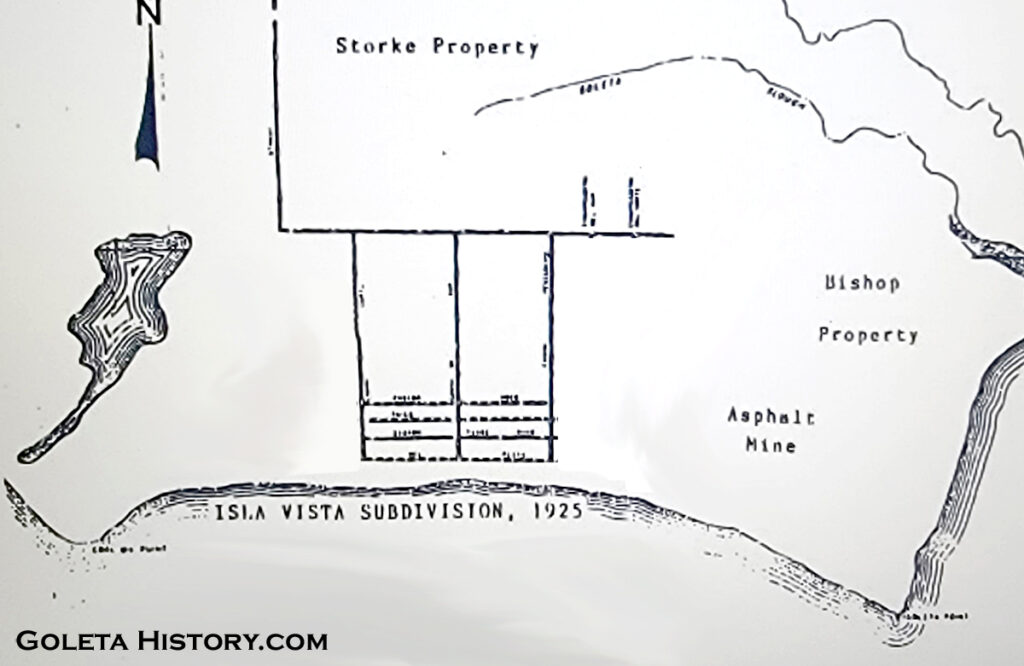

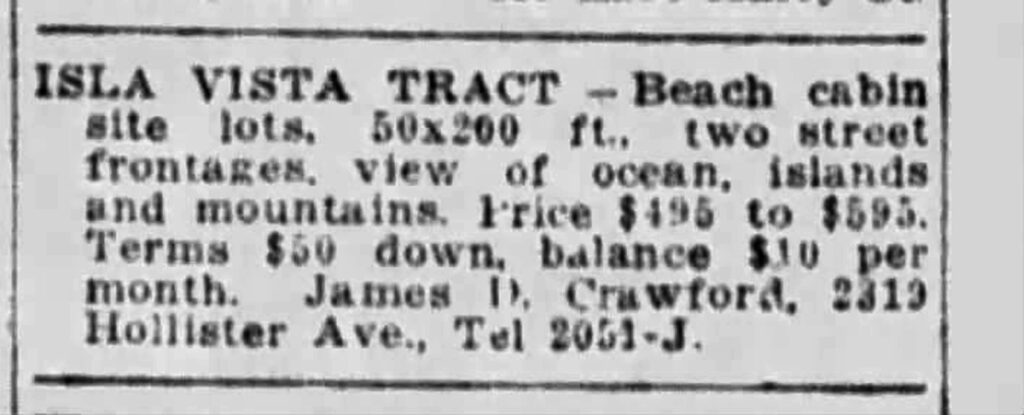

In 1925, the Ilharreguys laid out on paper their new subdivision that they named “Isla Vista”. Their real estate scheme was going to involve living on the scenic coast while enjoying the fortune of the oil industry. They divided the beach front into narrow 25 foot lots, and then the rest of the subdivision had standard 50 X 100 foot lots. They would drill for oil on the smaller lots, and if you owned any lot in the subdivision, you shared in the profits from an oil strike anywhere on the property. The lots were like shares in an investment. The more lots you owned, the greater the percentage of oil profits you would receive. Everyone’s a winner, if oil is found…..

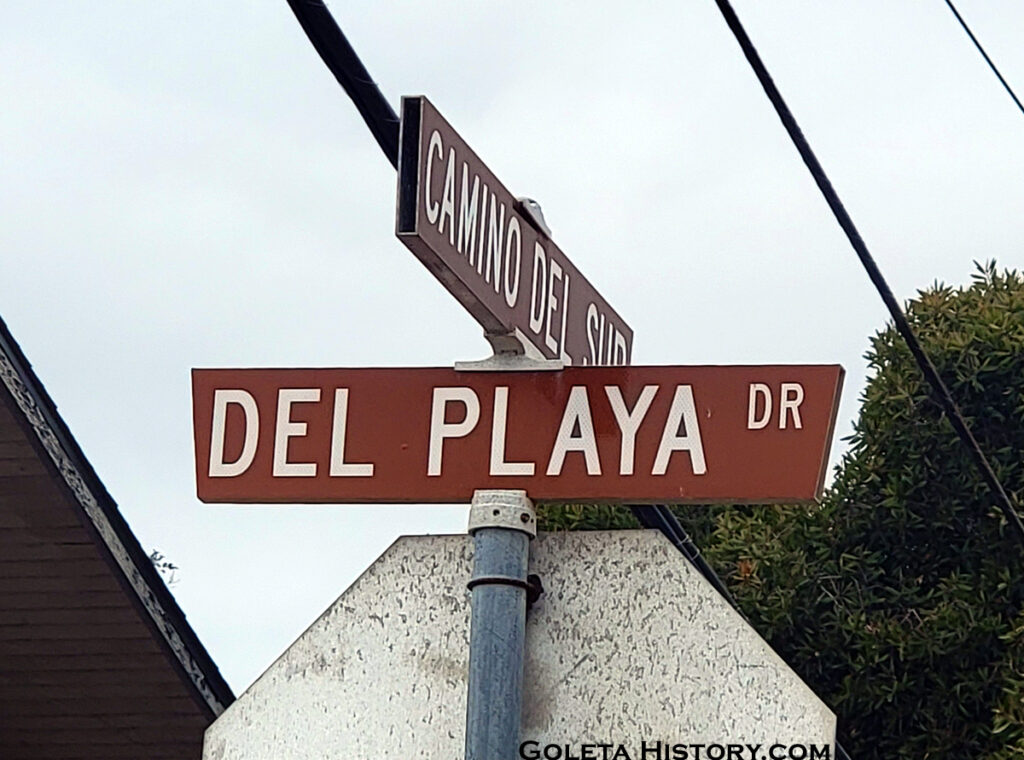

Santa Barbara had just survived the massive earthquake of 1925 and the city leaders decided to rebuild itself in a uniform Spanish Colonial theme. All new developments in the outlying areas followed their lead and the Ilharreguys thought it would be wise to choose Spanish names for their new subdivision as well. Unfortunately, they were clearly not fluent in Spanish, and the names they came up with were proof.

Isla Vista is grammatically incorrect, the premier ocean front road, Del Playa, is also grammatically wrong, and the meaning behind the name Pasado is anyone’s guess. But none of it mattered, the subdivision was quickly and easily approved.

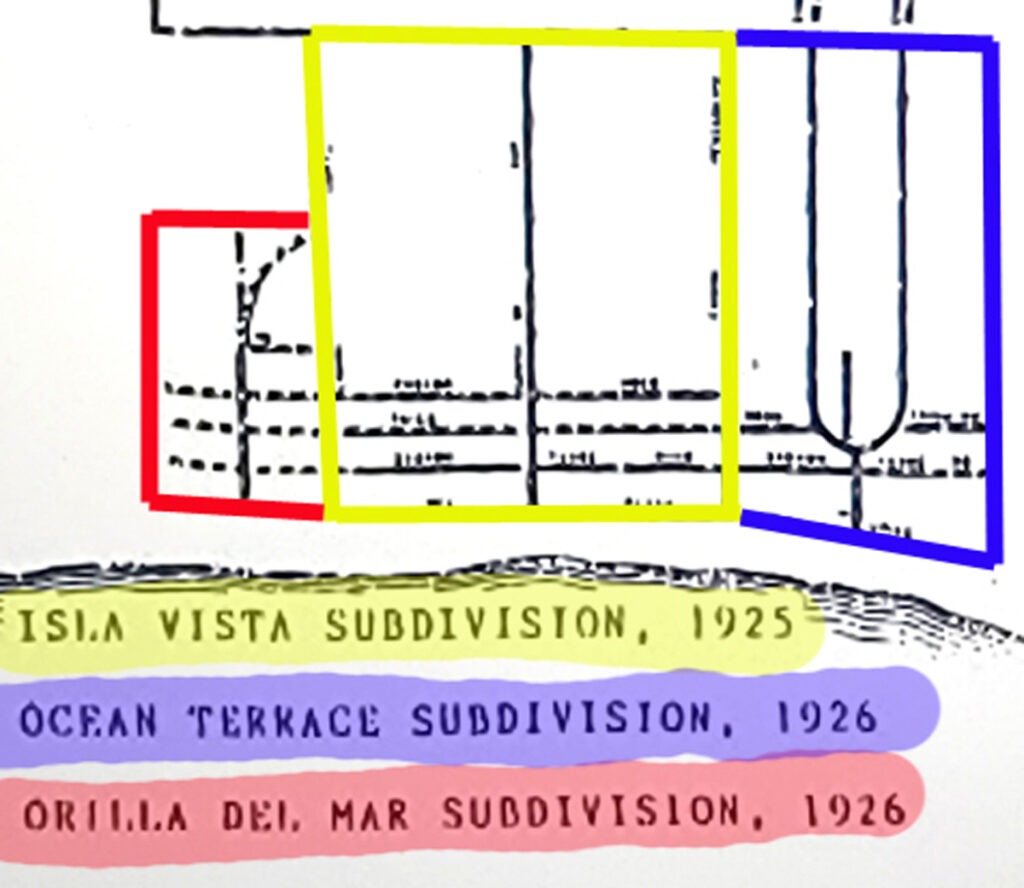

Their unorthodox idea of a wealth sharing neighborhood appealed to other “insiders” that heard about it, and within a year, both sides of Isla Vista were sold and subdivided. Two Santa Barbara lawyers bought the land east of Isla Vista, drew up adjoining streets and copied their narrow beachfront lots. The 2 roads that ran from the access road joined near the ocean making a loop that was to be the location of a park. They also chose Spanish names for all the streets but they gave their neighborhood an English name, Ocean Terrace. Later in 1926, another subdivision was planned to the west of Isla Vista by the Moody sisters, also of Santa Barbara. They both worked for the County and their father was a building contractor. They followed the street pattern but left room for an oceanfront park in between the oil lots. This neighborhood was named Orilla Del Mar, or Seashore. While all these plans looked impressive, only 3 roads actually existed. The rest of this was merely on paper as a real estate promotion, not an actual development.

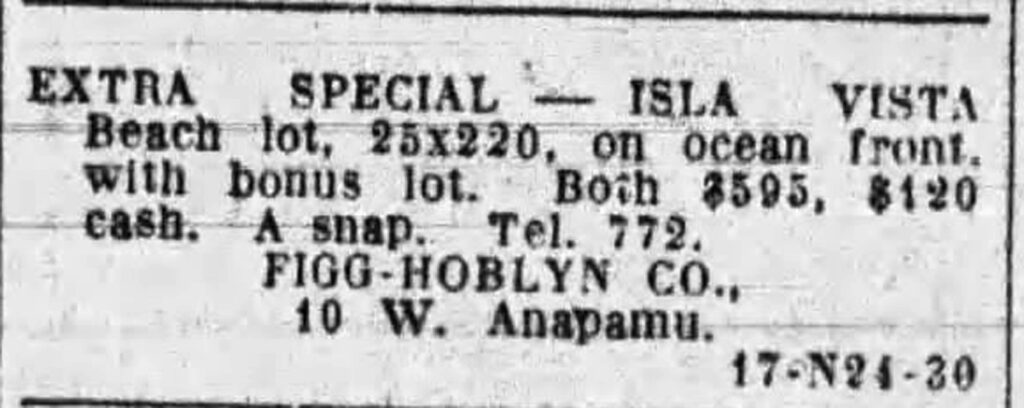

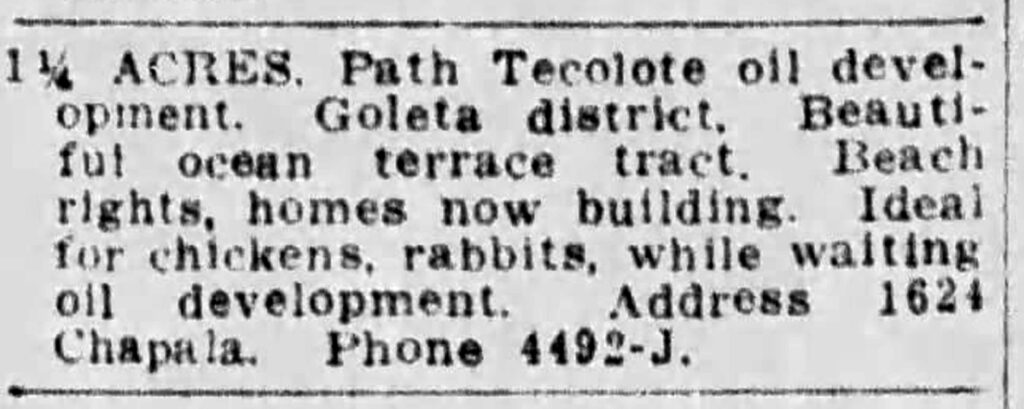

And promote they did! In 1926, the newspaper was full of great deals on real estate on the former Rincon Ranch.

Between 1920 and 1924 about 100,000 people moved to Los Angeles, mostly due to new water availability, the motion picture industry and multiple oil discoveries. This was the start of a decades long boom of growth. The Santa Barbara area also experienced a frenzy of developments and the Isla Vista tracts were right in the mix with local and out of town investors buying and reselling lots. Real estate promotions were nothing more than a plan on paper and a few stakes in the ground. Without potable water and the oil discovery that this promotion was built on, Isla Vista would remain worthless.

Isla Vista was the first subdivision performed in the Goleta Valley. No plans for water, electricity, road building, or sewage were made, this subdivision was “speculative”. In 1928, Isla Vista looked about the same as it had for decades. Desolate, waterless and empty, except for a couple hardy bean farmers and their chickens and goats. Some roads had been lightly scratched into the hard soil, mainly to allow the delivery of water. While it looked like the dream had seized up, it still existed on paper. It just needed a little oil to get things moving again.

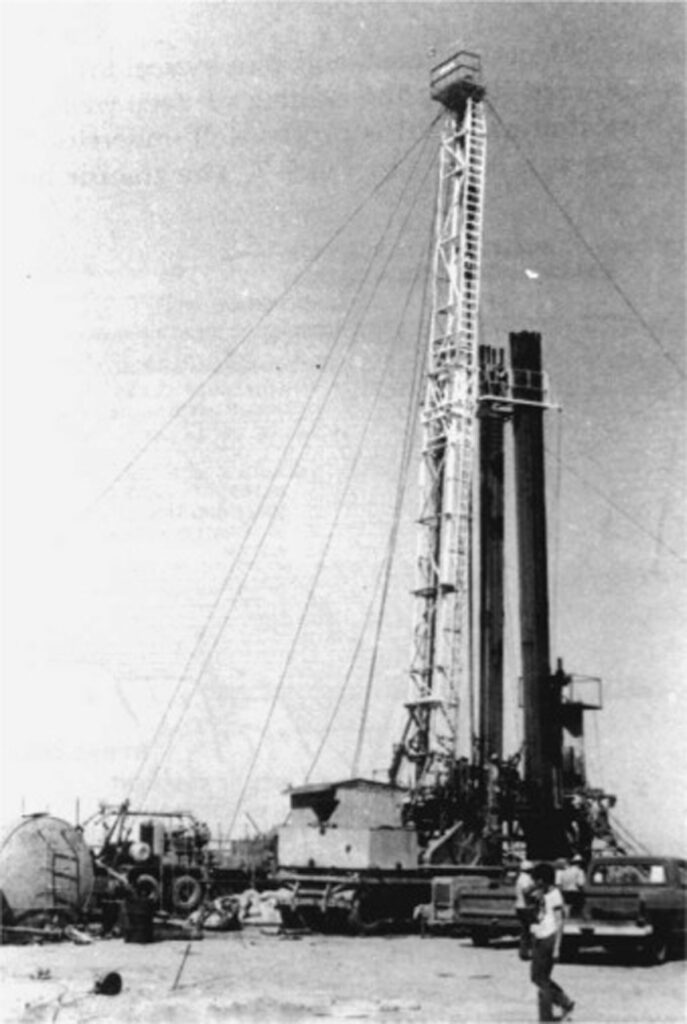

While living next to an oil well sounds horrible to us today, it was not uncommon in Southern California at this time. Since oil played a crucial role in the Isla Vista dream, exploration was encouraged. Throughout the 1930s, several attempts were made by different companies in the Isla Vista area. A few companies found a little oil, but not enough to pursue it any further. The lots that had sold remained undeveloped and some of the lots that didn’t sell had to be deeded to the state to pay off taxes.

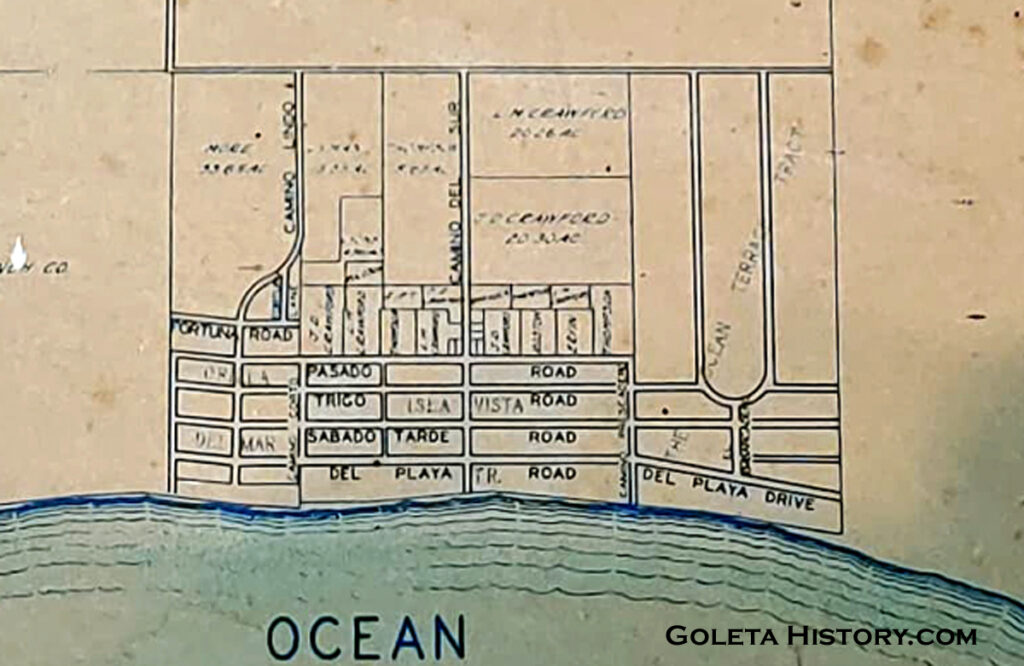

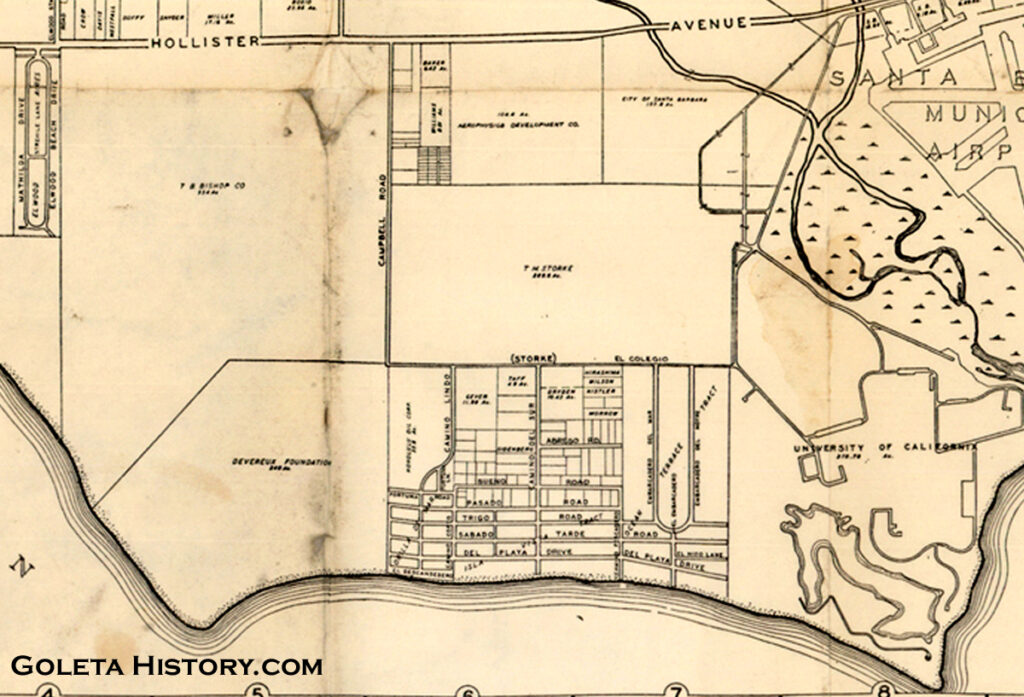

This surveyor map from 1935 makes Isla Vista look like a legitimate little community. Plenty of city streets laid out in a nice orderly manner with their fancy Spanishey names on full display. The County never required the three subdivisions to use a common street layout so a few of the streets didn’t quite line up right, but, hey, even beautiful Santa Barbara has that problem!

This shot from 1938 shows what Isla Vista really looked like. A few of the subdivision roads actually existed, mixed with a mish mash of trails, shortcuts and pastures. And watch your step, no sewer system existed so sewage and garbage were disposed of in a variety of ineffective manners.

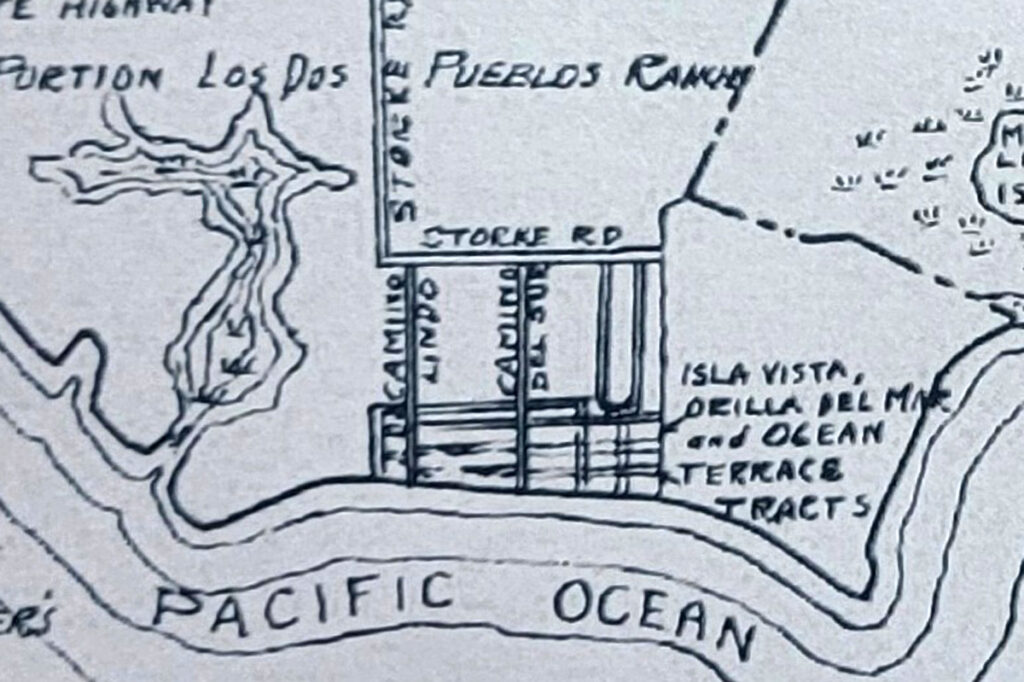

This 1939 map drawn by Owen O’Neil shows a more realistic appraisal of the Isla Vista area. He mentions all three development names, but only a couple street names are noted and the old Rincon Ranch road is labeled Storke road.

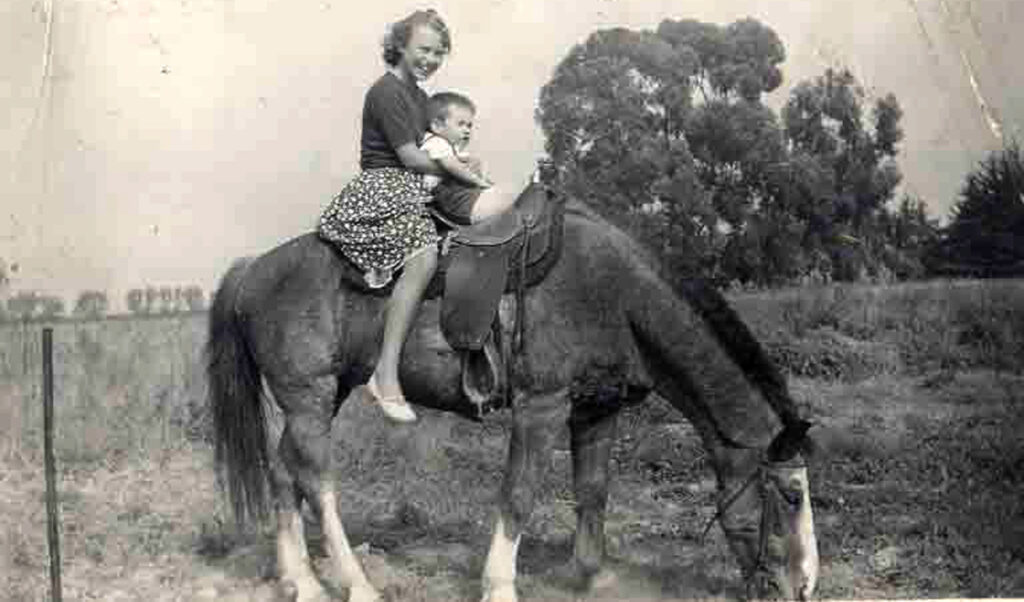

Meanwhile, despite all the investors struggles and the lack of modern conveniences, a few families managed to live happily on the undeveloped subdivisions. This 1942 photograph labeled “Ocean Terrace”, shows young members of the Munoz and Cuevas families enjoying the freedom that wide open spaces can bring to a child. But the Eucalyptus Curtain behind them concealed a world of change that was about to come in their direction. The United States had gotten into World War II and a new Marine base was being constructed as fast as humanly possible.

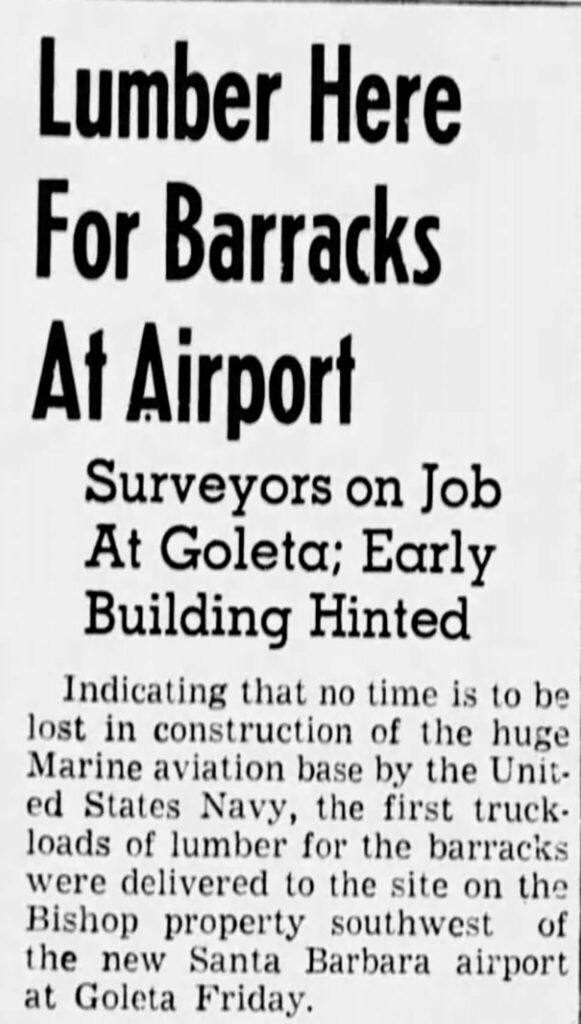

In 1938, the property to the east of Isla Vista was a huge expanse of barren land looking for a purpose. The war brought that purpose.

The swift construction of a Marine base turned a treeless, waterless property into a valuable asset.

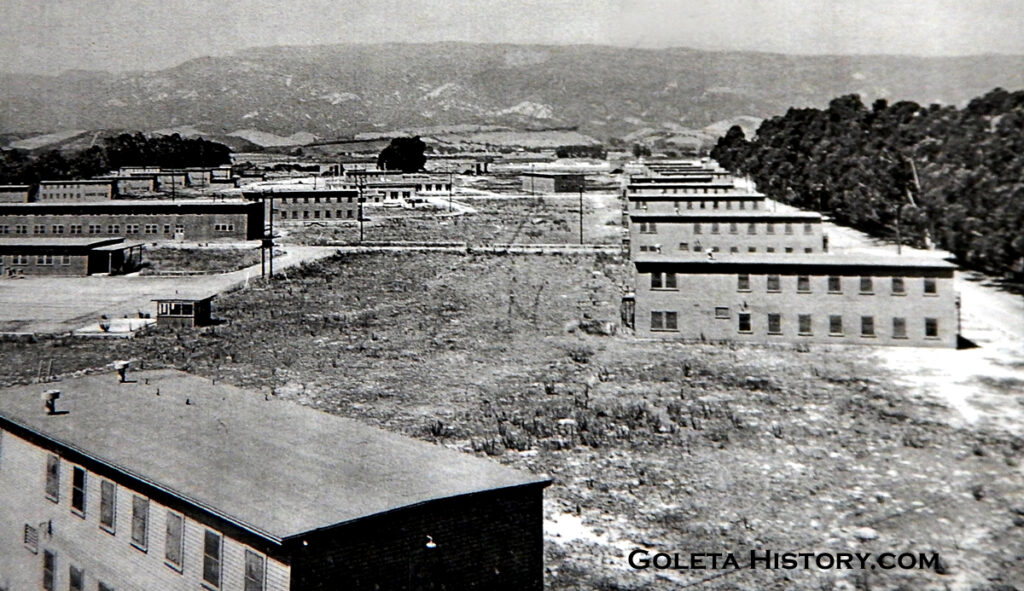

By 1943 that barren land was the site of a small city, quickly built just for the United States Marines. Over 100 wooden buildings including barracks, mess halls, chapels, theaters, laundry, administration and other facilities were all built on the empty mesa. But the new base next door didn’t change anything in Isla Vista, other than an unofficial horse stable a few officers bought to enjoy horseback riding in their downtime.

After the war ended, the Marine base was closed down. The Bishop Ranch didn’t want the land back, so it was set to be sold on the open market. While the Marines time in Goleta didn’t directly affect Isla Vista, the next occupant certainly would.

Thomas Storke and a group of his influential friends were able to persuade the government to sell the whole area to the University of California for $1. They took over the real estate and the now abandoned buildings with plans for a beautiful new UCSB campus that would have plenty of room to grow. The hard won decision to move the college from its Riviera location to Goleta was criticized by some, saying it was moving, “the campus with a view, to the campus in the slough”.

While all the wheeling and dealing for the University was going on, property owners in Isla Vista kept busy trying to finally cash in on their investment. A couple more oil companies tried again to find oil using new and improved technology to drill deeper down than ever before. While they did find minimal success, it still wasn’t worth the effort, and the oil companies lost millions of dollars. Now it seemed the Ilharreguys’ dream of an oil rich community was officially dead. But some good news came in 1949 when the Cachuma Dam project was approved, promising access to water in the near future. Running water and being located next to a new University would be very good fortune for Isla Vista property owners.

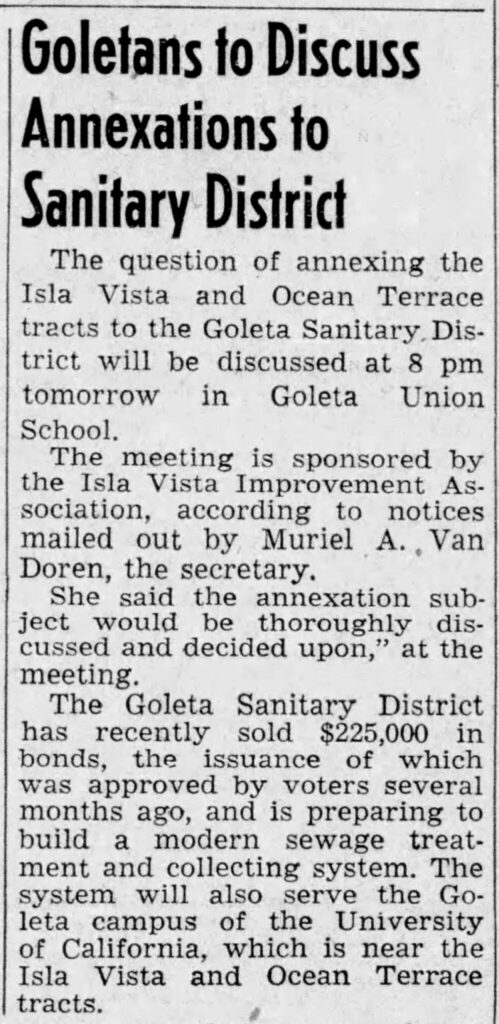

With news of the university becoming official, property owners formed the “Isla Vista Improvement Association” and began petitioning officials to get a sewer system in place. The first influence their new neighbor had was a positive one since UCSB was a powerful ally for getting the mesa hooked up to much needed utilities. But the narrow streets that didn’t line up and the undersized lots laid out for the 1920s oil scheme would come back to haunt the planners.

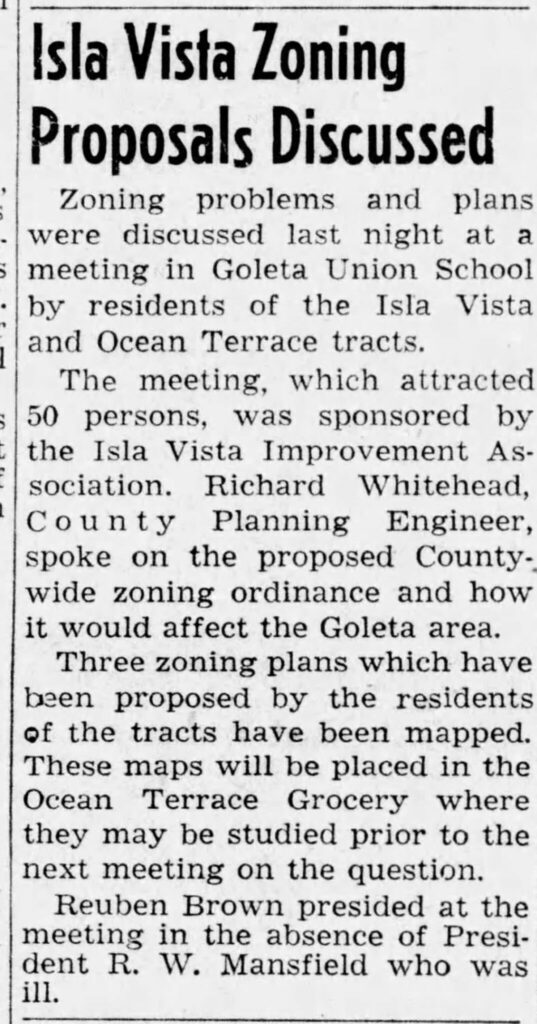

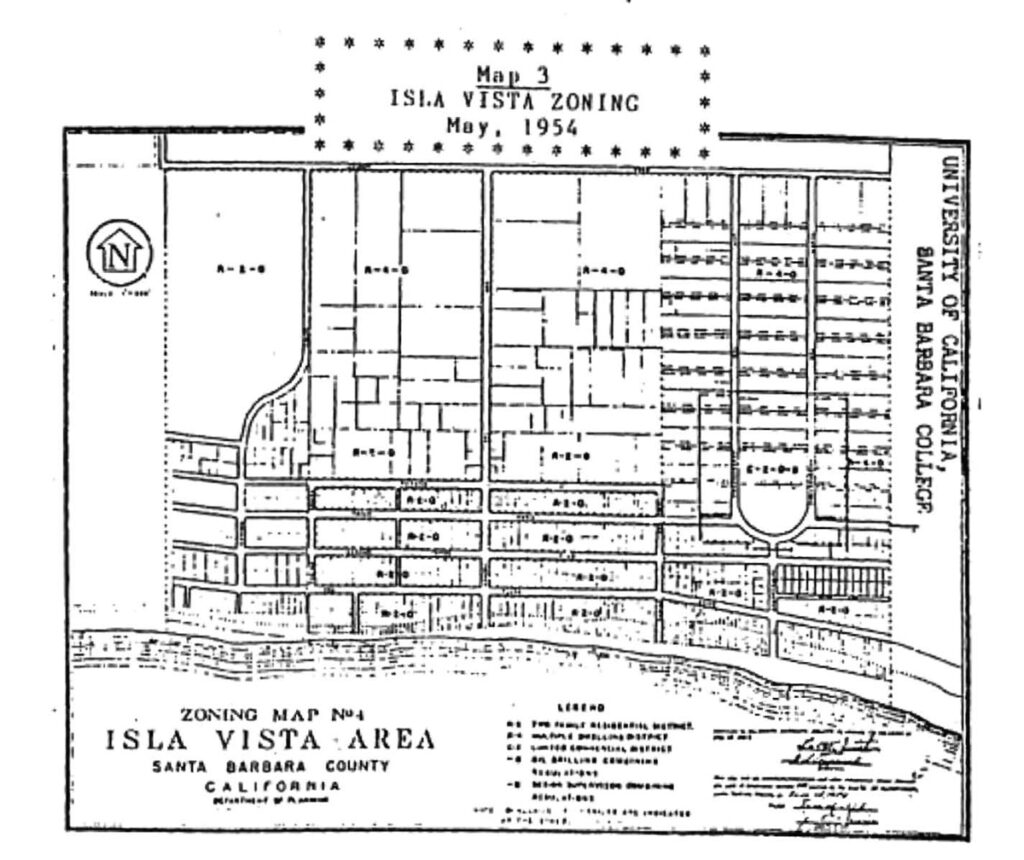

Before Isla Vista could become a community, it needed zoning. With the university coming to the area, county officials now realized they had to deal with this ramshackle little community that had always been overlooked. The County Planning Director saw the narrow streets and tiny lots and determined low density would be best there. But the property owners saw things differently. Remember, this was an investment community born of the desire to make a profit. The 330 acres of Isla Vista were owned by 500 individuals, most of them lived out of town and they wanted a long awaited return on their investment. Surprisingly, the majority of the owners that actually lived there also wanted to maximize their profit! They all seemed to agree, if they couldn’t get rich from oil, they would get rich by maximizing the value of their land. Higher density meant higher land value so they pushed the County for as much multiple residential zoning as possible.

After multiple meetings, a zoning map was finally finished. About half of Isla Vista was zoned multiple residential allowing 4 or more units each lot, the loop on “Ocean Terrace” was zoned commercial, and the rest was all zoned for one duplex per lot, including the tiny beachfront lots. So every property owner could build a duplex and be a landlord. At max capacity, Isla Vista could house 13,000 people in a half square mile, 43 folks per acre. More density than anywhere west of the Mississippi at that time. Surprisingly, the county was fine with that, but they did insist the roads be widened. 500 property owners were persuaded to donate 10 feet of street side property to the county and the roads were widened.

While progress was being made on paper, an actual site visit by the County Health Department in 1953 proved the community had a long way to go. The roads were soft dirt, the majority of the housing was sub-standard, nearly all were using bottled water and nearly half the homes had outhouses for toilets.

A majority of the residents had livestock, (over 1,000 animals, not counting dogs and cats!) and garbage was either burned, buried or fed to the animals, resulting in garbage piles all around. This would not do for the neighboring community of a big university.

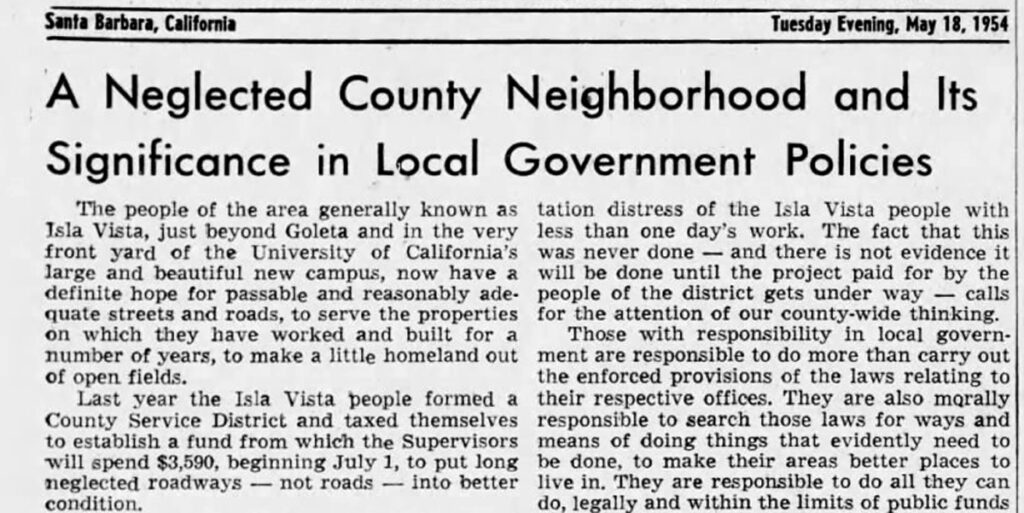

But the citizens of Isla Vista willingly taxed themselves and found a way to get their community in order. Tom Storke wrote an editorial in his News Press, praising their efforts and scolding the county for not being more helpful. Storke was surely concerned about Isla Vista getting modernized, since his new location for the university was called the “most isolated college in higher education”. In fact, for the first few years after the campus opened in 1954, most of the students still lived in Santa Barbara.

Throughout the late 1950s, the student population increased and new buildings were quickly built on campus. Meanwhile, Isla Vista was working hard to get their act together. A sewer system was finally installed, old shacks were being demolished and properties were being cleaned up. Some property owners wanted to move old houses from Santa Barbara to their Isla Vista lots, but most residents protested against that and the university agreed. UCSB requested that the county monitor all the development on the perimeter of the campus, so the county passed a design regulation to cover all of Isla Vista. But the county also allowed exceptions to most every request on lot density to allow for much needed university housing. This would become a trend that could not be reversed.

The tireless efforts of the Isla Vista property owners was beginning to pay off and property values skyrocketed. The entrance road name was officially changed to El Colegio Road. By the late 1950s, even UCSB couldn’t afford the land to build a fraternity and sorority row, leaving them to fend for themselves in Isla Vista. This would cause problems for future residents that had to live next door to the Greek houses.

1959

UCSB has had a housing problem since the day it opened. In 1954, very little housing existed in Isla Vista and even the whole Goleta Valley. As the enrollment increased, the housing could never keep up. When there was a housing boom in Goleta in the late 1950s, the majority of those were filled with employees of the new research and development companies opening in Goleta. To make matters worse, the UC Regents announced they were increasing enrollment of UCSB to 10,000 students.

The university came under fire for not providing safe housing for its female students. Multiple male students could pile into small houses or apartments, but the college was held accountable for the safety and supervision of the female students. To remedy this, the Dean of Students recruited a reputable Los Angeles developer to build some apartment buildings specifically for female students. The Tropicana Gardens, Fountainbleu and Westgate apartments were opened specifically for females with security entrances, pools, cafeterias and even a beauty parlor.

Around this time the university also hired a reputable architectural and planning firm from L.A. to help formulate a future housing plan. The “Santa Barbara Campus Community Study” took a year to complete, and when it was unveiled it proposed a stadium, a golf course and turning the slough into a small boat harbor. Isla Vista however, still presented a problem, even to these highly acclaimed experts. With the over 500 separate land owners, poorly designed streets, expensive utilities and high taxes, the expert suggestion was to designate it an “Urban Renewal District”, bulldoze it and start from scratch.

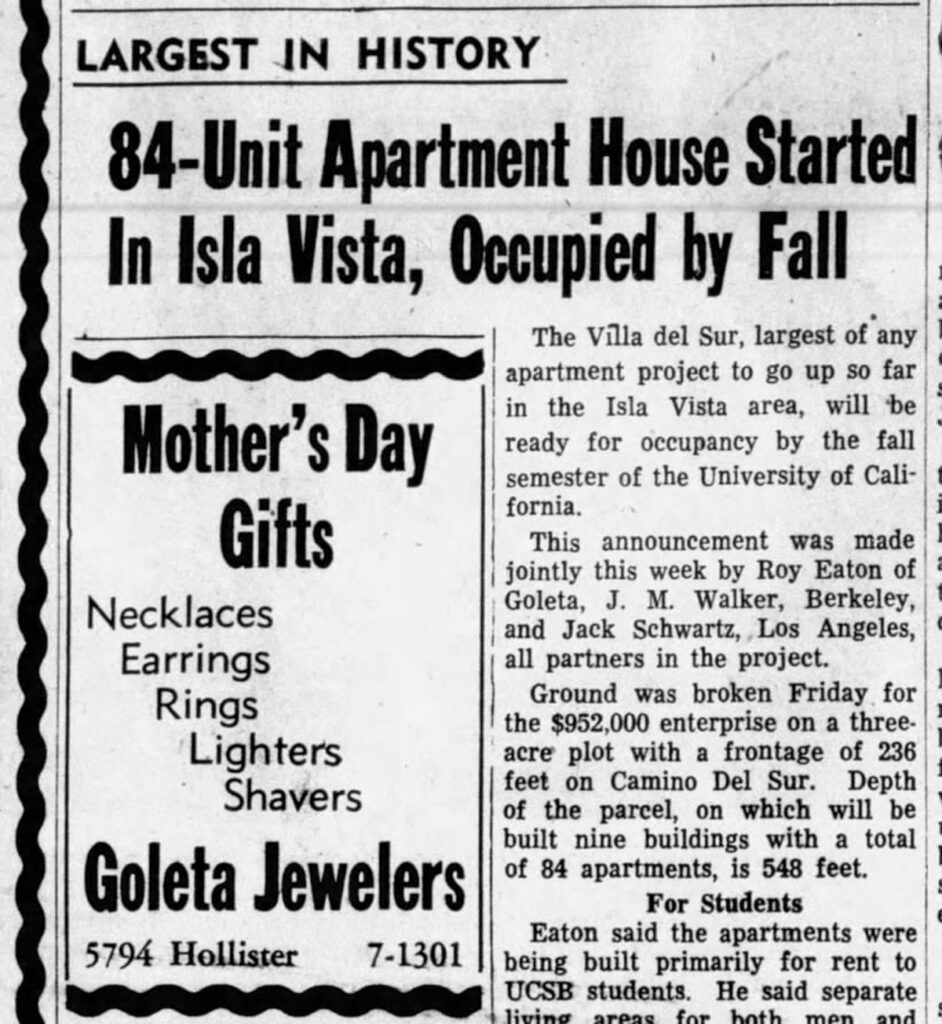

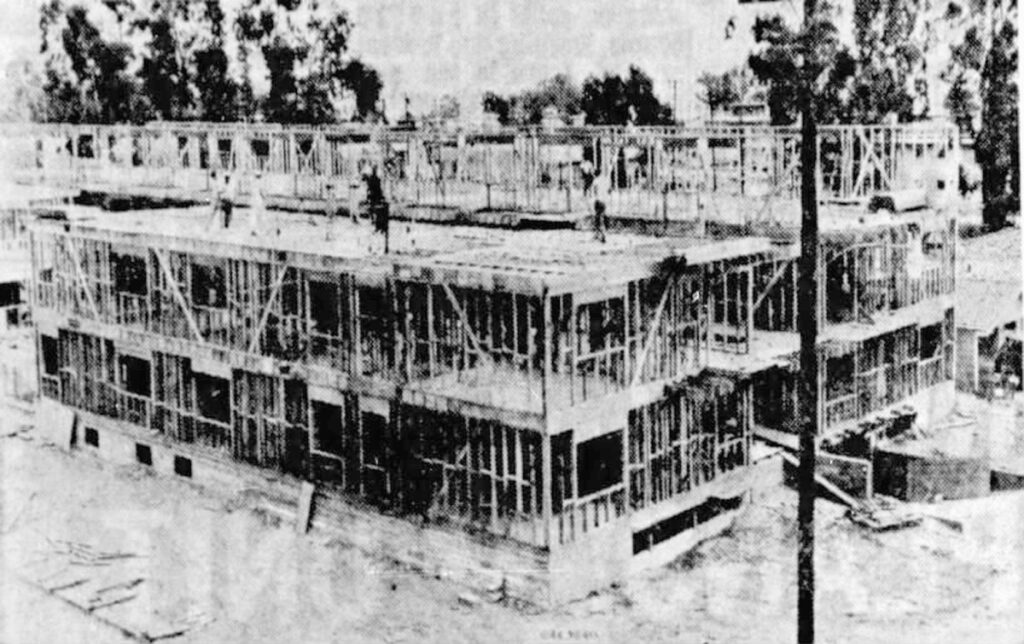

But it was too late for that. The door had been opened for less reputable and more aggressive developers to come in. Before long, apartment buildings were popping up and the overwhelming demand for more student housing forced the county to agree to only one parking space per unit.

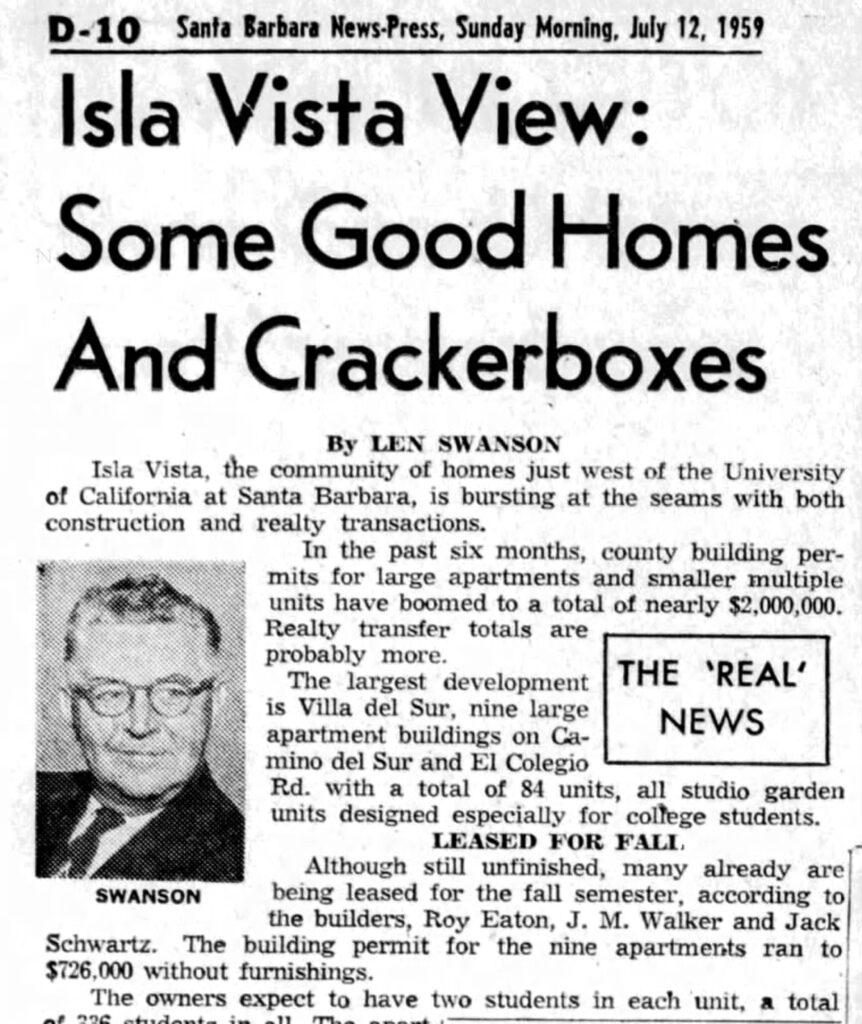

An article written by a popular real estate columnist in 1959 pointed out how Isla Vista was an unplanned “hodge-podge”, full of developers out to make a quick buck building “cracker boxes” with no style. The dream of Isla Vista becoming a charming seaside community was drifting further out to sea.

The 1960s brought more of the same. Aggressive developers from out of town had joined the Isla Vista Improvement Association and they had a dominating influence on the planning. Jack Schwartz was the most prominent developer and he led the others with “bulldog tactics”.

By 1967, Schwartz was instrumental in the approval of a new ordinance for the already overpacked neighborhood. An “S” designation for student housing would further reduce the parking requirement for new developments to less then one space per unit! An obviously bad decision that would haunt the community forever.

Schwartz also led the charge to change duplex zoned parcels to multiple unit zoning. One realtor that specialized in Isla Vista sales was quoted as saying, “We’ll build until we run out of room. Then it will go to high rise apartments.” He wasn’t wrong.

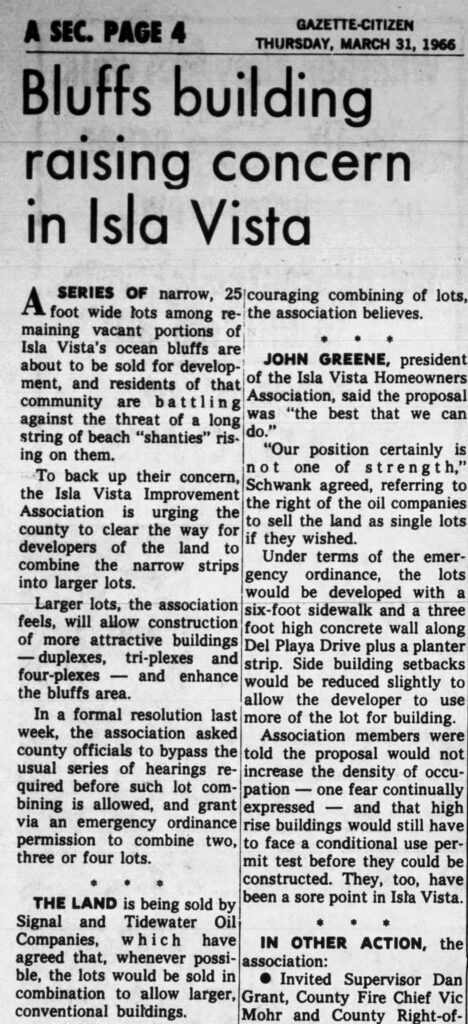

Those tiny little blufftop lots the Ilharreguys had laid out for oil wells were sold in groups to make them big enough to build apartment buildings on them. The concern mentioned in this article should have been for the constantly deteriorating cliffs and the danger of building in such close proximity to them.

Meanwhile, the commercially zoned property around the Embarcadero Loop failed to develop in an orderly fashion and was also a random hodge-podge of style and uses.

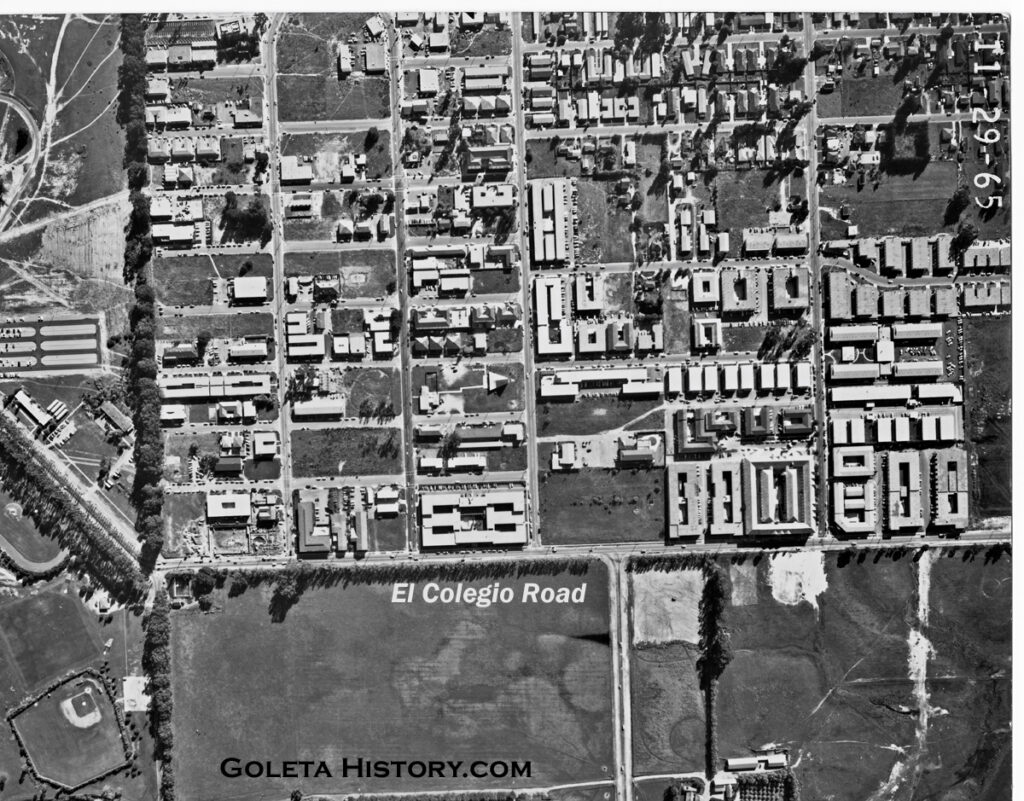

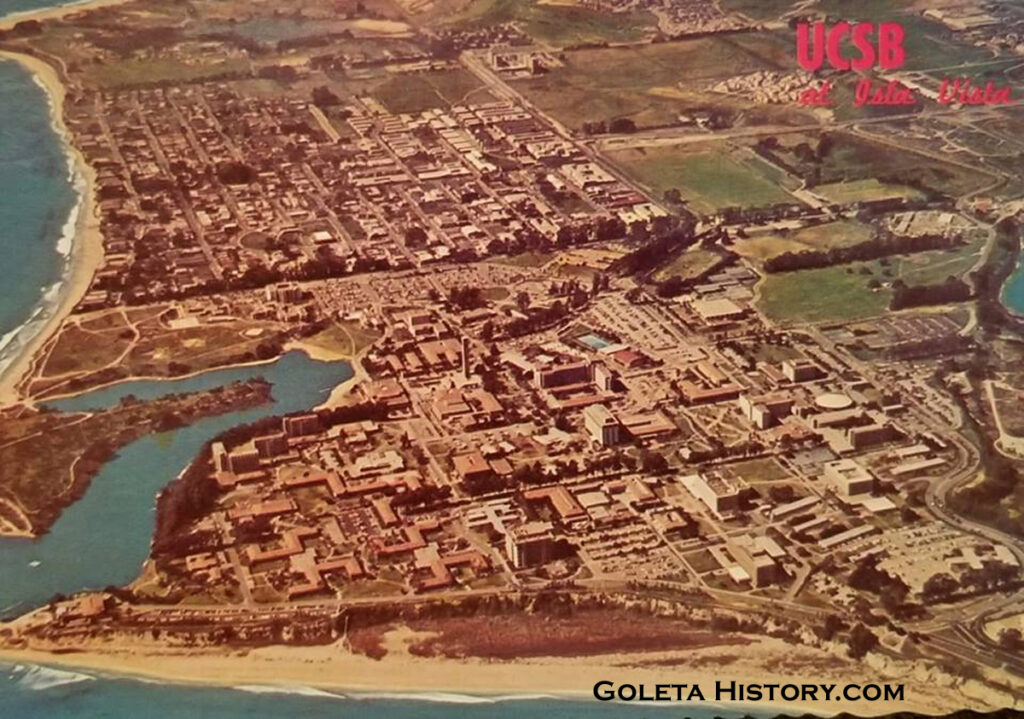

This 1965 image shows there were still more vacant lots to be built on. A volatile combination of greed and power was building this little village by the sea. The university and it’s unending desire to enroll more and more students and the developers that were eager to provide that housing for the ever increasing population. Meanwhile, a tidal wave of social change was about to break on Isla Vista.

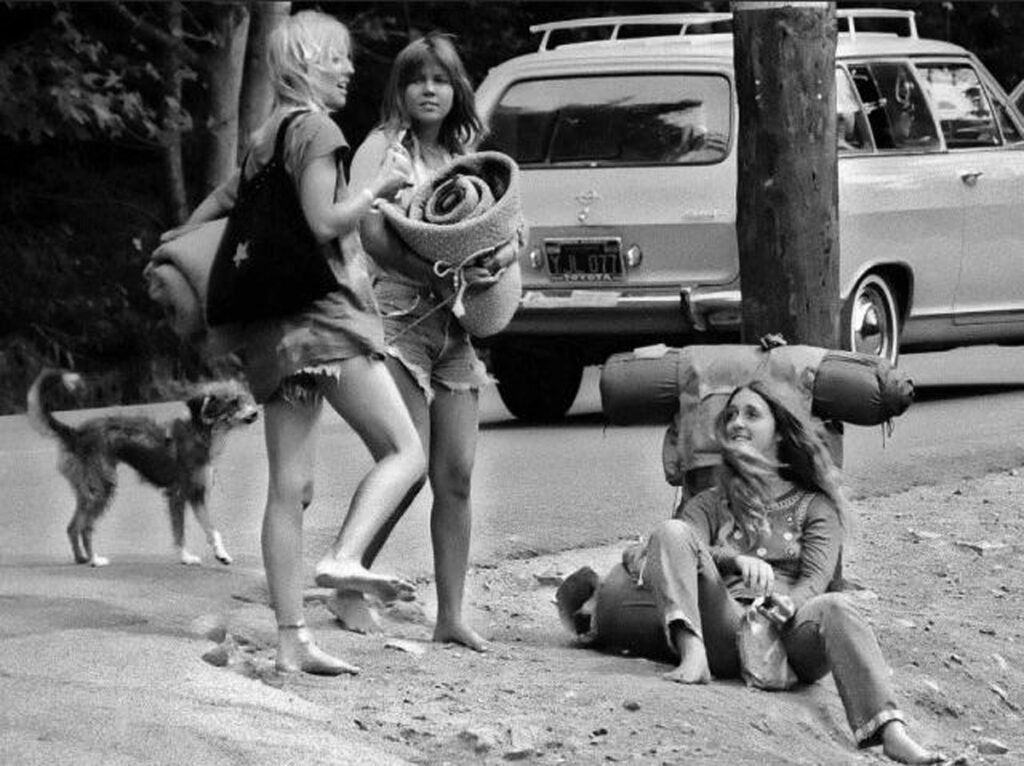

By the mid 1960s California was a boiling pot of youth culture. Isla Vista became a natural stopping point for hitchhikers that were traveling between Southern California and San Francisco. It’s beautiful location by the beach, lack of oversight, and booming population of young likeminded people made I.V. a groovy destination for hippies. A great place to “Turn on, tune in, and drop out”. Local folklore says that Jim Morrison of The Doors wrote the song “The Crystal Ship” while tripping on acid and staring at the bright lights of platform Holly, just off the Isla Vista coast.

Due to the close proximity of a major university, some big name counterculture speakers came to the coffee houses and parks of Isla Vista, attracting large crowds of energized youth. The Vietnam War, the mandatory draft, the sexual revolution, the civil rights movement, experimental music and experimental drug use were all factors that contributed to the social climate in the overcrowded little beach town. Folks in Santa Barbara and Goleta became uncomfortable with all the open drug use and drug dealing, so a heavy police presence began appearing in I.V.

When the Magic Lantern Theater was raided by authorities and temporarily shut down for showing obscene films, tension between the students and the “Establishment” climbed higher.

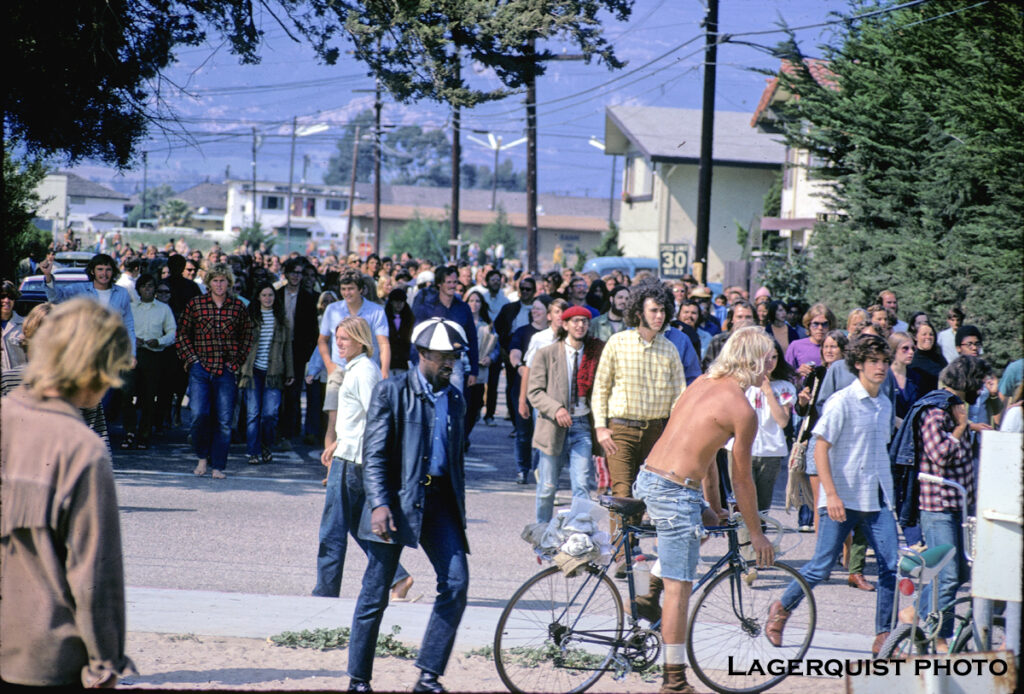

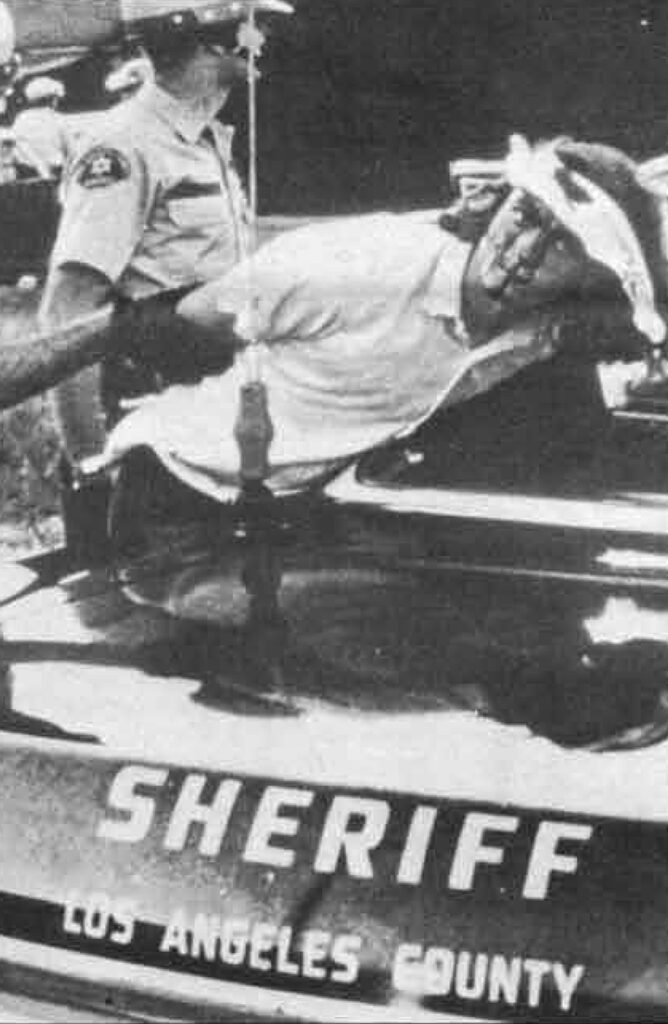

All the tension through the end of the 1960s came to a head in 1970 when Lefty Bryant, a popular local activist, was arrested. A large, angry crowd formed in the Embarcadero Loop and started vandalizing property and real estate. Local police were reinforced by an overly aggressive police force from Los Angeles, setting off a series of violent riots in Isla Vista.

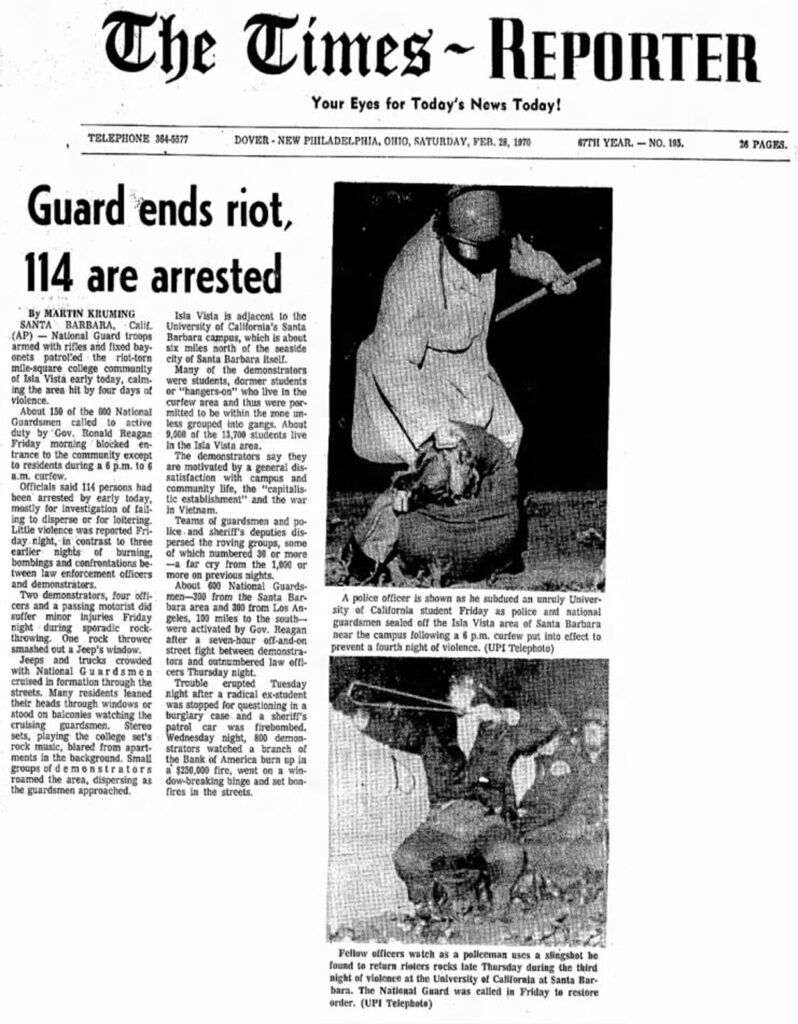

The ongoing riots built up to a frenzy, resulting in the burning of the Bank of America in Isla Vista. This event made headlines across the nation and resulted in a heavy handed military police presence. Months of violent protests and riots dragged on through the summer of 1970.

A lot has already been written about the I.V. riots and the burning of the bank, so we won’t go into much more detail here. This classic Joe Melchione photo captures the essence of it all. Riot police in the foreground, preparing to face the students in the distance, with the cheap Isla Vista apartments as a backdrop. If you want to learn more about the riots, click Here and Here.

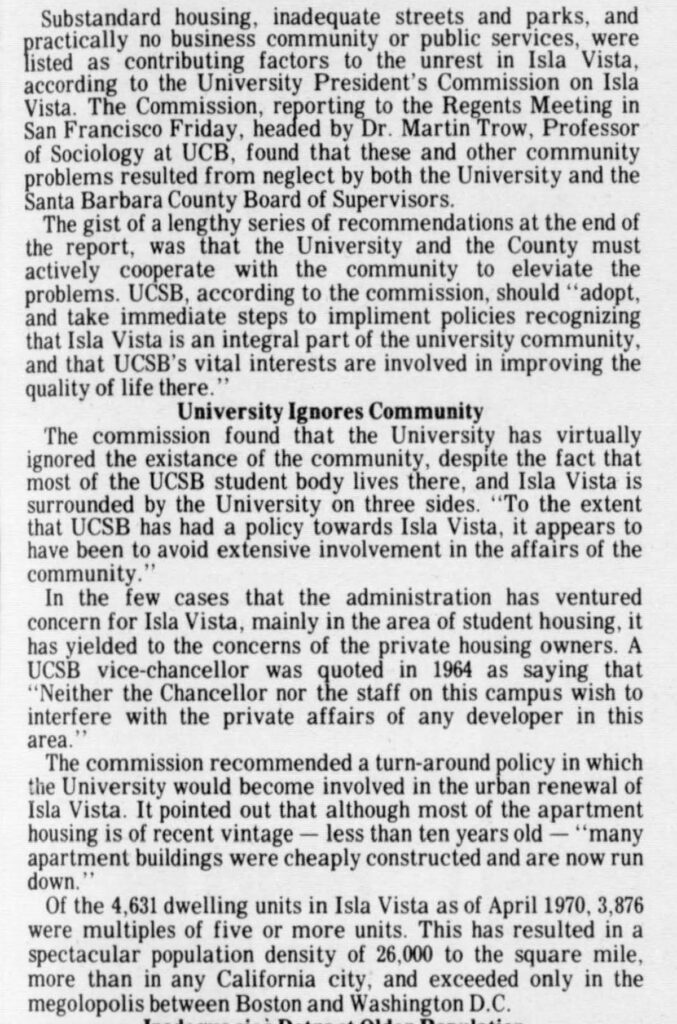

Eventually a student would be killed by police, causing even more riots and resulting in Governor Ronald Reagan sending the National Guard in to get control of the little beach town. More civil unrest happened around the state, and many people thought this was the beginning of a civil war, but thankfully things soon settled down. After the riots, the UC Regents issued the “Trow Report”, that had recommendations for the university to provide more community services, more housing for the students in Isla Vista, and to limit the student population.

Limiting registration at UCSB was probably easy to do after newspapers all across the United States had been featuring college aged kids getting brutally beaten by authorities for months on end.

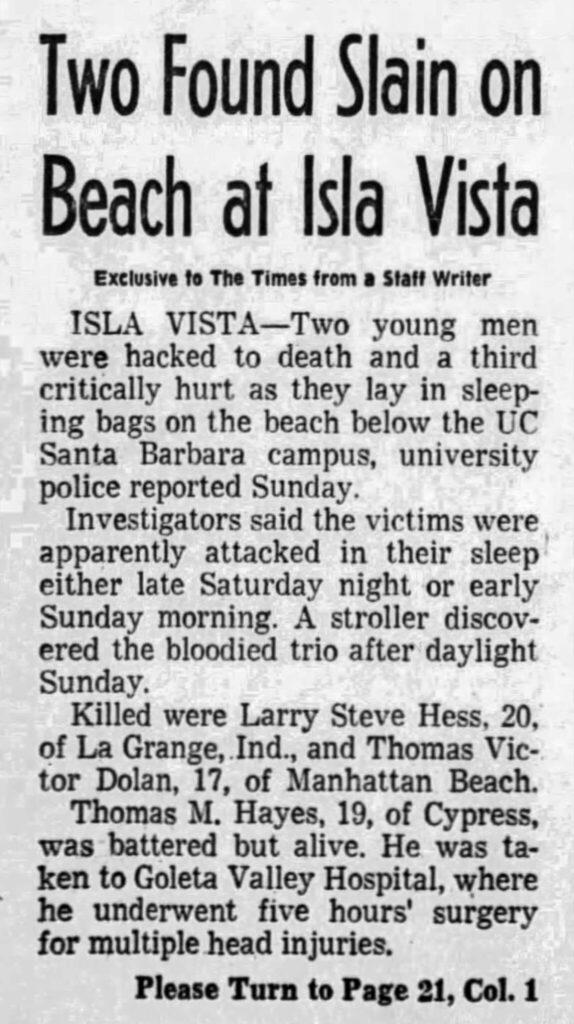

To make matters worse, a couple months after the riots settled down three young men sleeping on the beach at Isla Vista are brutally attacked, two of them dying on the scene. Nothing was stolen from the victims, and the case was never solved. Another reason the enrollment at UCSB took a dive for several years to come.

The Trow Report discovered what any student of history would have already known. The overbuilding and overcrowded conditions in Isla Vista were a big reason for the social unrest and it put the blame squarely on the university and the county. The report was especially hard on UCSB, pointing out how the university had ignored Isla Vista and they needed to actively participate in improving the quality of life there.

Several other studies were implemented and the general conclusion was that the citizens of Isla Vista had no control over their own community. Moving forward, Isla Vista received funding from the county and the university to create more civil organizations, like a medical clinic, a credit union, a community council and a foot patrol. The revitalized community was thought of optimistically as a “laboratory of social change”.

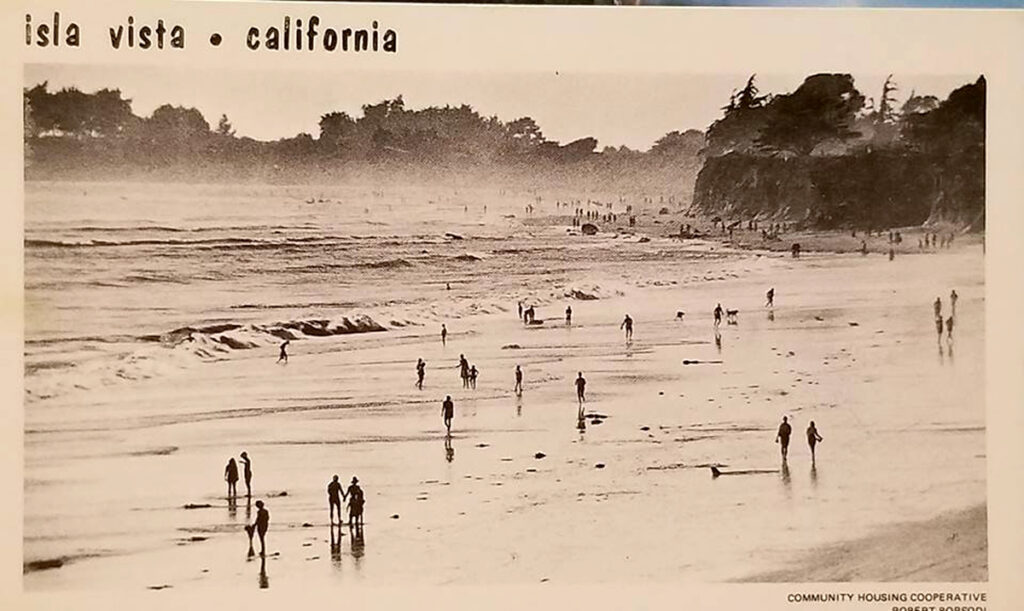

A renewed optimism and sense of community came to Isla Vista, as can be seen with these cool postcards.

So many cool things in this postcard. Notice the shape of those surfboards, the smiley face on the lifeguard tower and the teepee on the bluff.

Teepees (or tipis) started popping up in the 1960s. A perfect setup for a hippy on the move, they could simply pick up their tipi and move if or when the landowner objected. In the late 1970s, Carmen Lodise says there were over 60 tipis in I.V., a direct response to the huge rent increases caused by the skyrocketing enrollment numbers at UCSB. Over 20 of the tipis were in “Tipi Village”, on a vacant lot on Sueno Road. They lived there happily for a while, eating vegetables from community gardens, and claiming it was low impact living, environmentally sound and better for the planet. Unfortunately, some neighbors disagreed, and the authorities shut the village down for sanitation reasons, despite several organized demonstrations to save them. Today there is a sign on the site, commemorating the Tipi Village.

A lot did change for the better in Isla Vista in the coming decades, but the underlying fabric of the community was profit, from its inception. The narrow streets, overbuilt lots and lack of parking continue to be problematic issues to this day.

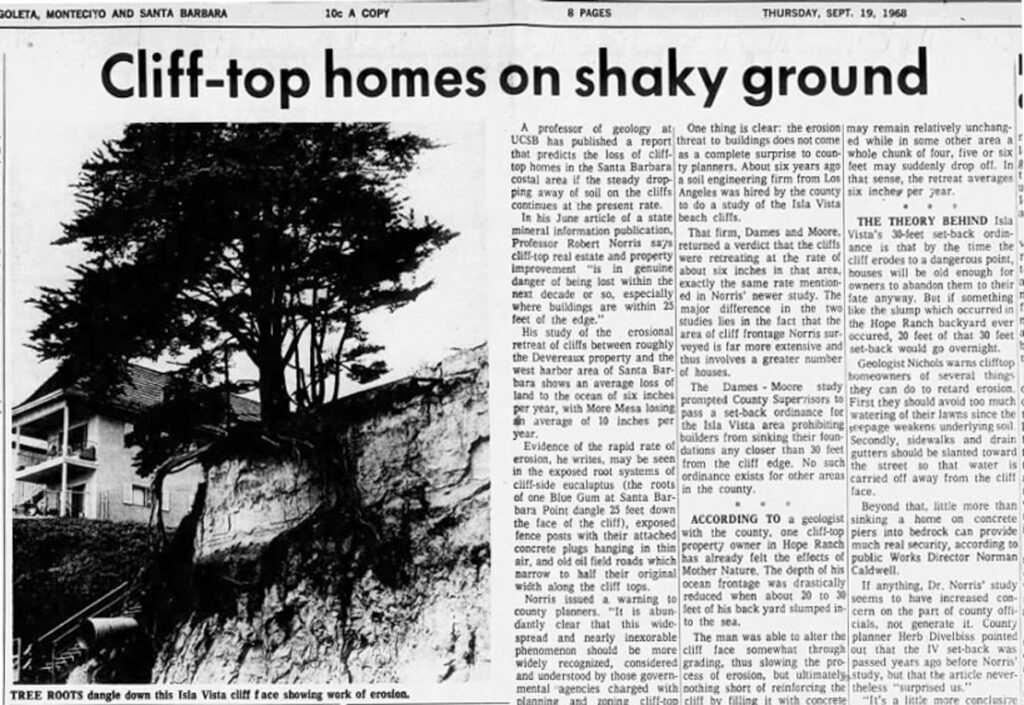

Another long lasting product of the greed fueled overdevelopment are the unsafe conditions on the Del Playa bluffs. This story from 1968 mentions an earlier report from 1962 that determined the cliffs were eroding rapidly, well before most of the building along the bluffs was even started.

By 1971, most of the tiny, oil drilling lots on the Del Playa bluffs were built on, most dangerously close to the edge. Most didn’t take advantage of the lot space towards Del Playa, probably to allow for parking.

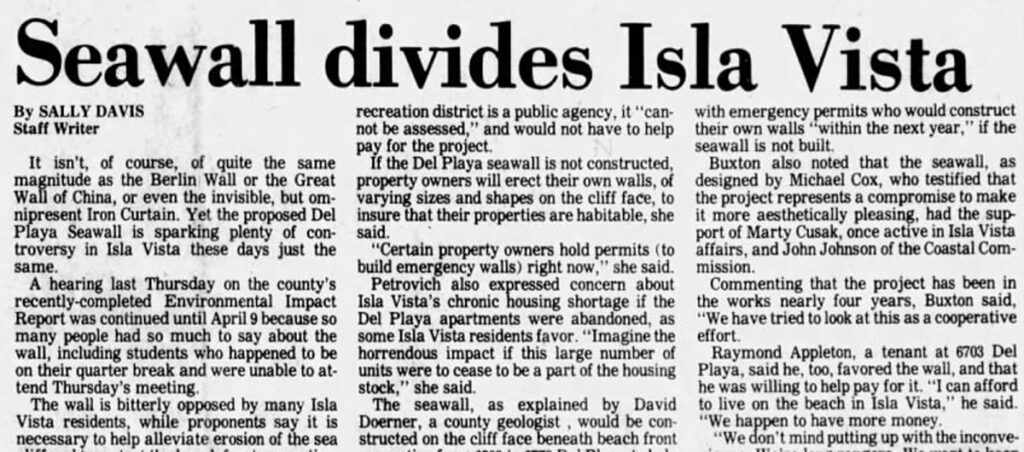

The cliff erosion and what to do about it has been an issue of debate for as long as there has been housing on the blufftops.

Mother Nature doesn’t seem to care, one way or the other. She just keeps doing her thing.

But time is running out for a lot of these units. For more info, the late Art Sylvester did an unparalleled study of local beach erosion, including the I.V. bluffs. See it HERE.

Through the years, several attempts to make I.V. a city have failed. When Goleta finally became a city, they went to great lengths to ensure the troubled Isla Vista was not within their city limits. With such a fluctuating population every year, it will probably never be anything more than an unincorporated bedroom community for UCSB students. Fortunately, community organizations still play a large role in Isla Vista today and the beachside location still makes it a lovely place to live.

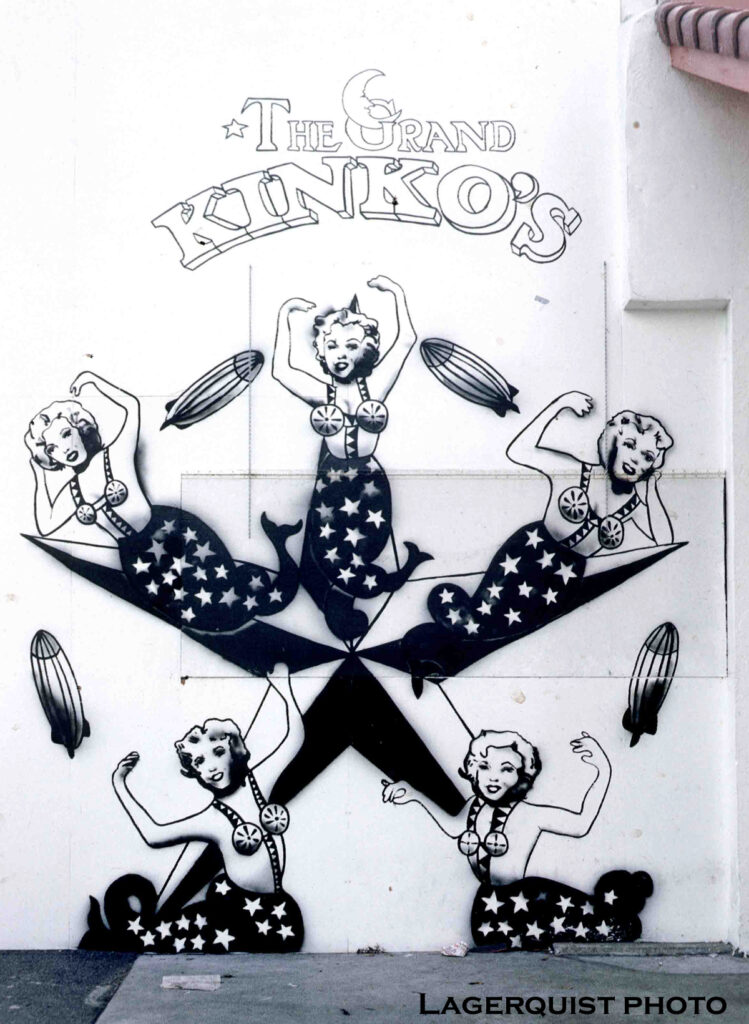

The young energetic population of Isla Vista has never been short on creativity. Lots of famous rock bands like Rebelution, Lagwagon, Ugly Kid Joe, Jack Johnson and Iration all say they started out playing parties in I.V. Several very successful businesses also started on these crowded streets. A kid with frizzy red hair nicknamed “Kinko” got a $5,000 loan from the Bank of America in 1969, right before it was burned down! His business grew to be worth billions before being bought out by FedEx.

Another very popular local business started in I.V. The owners chose the name Rusty’s because the sign on the building was already there. They simply cut the roast beef off and started making the best darn pizza in town.

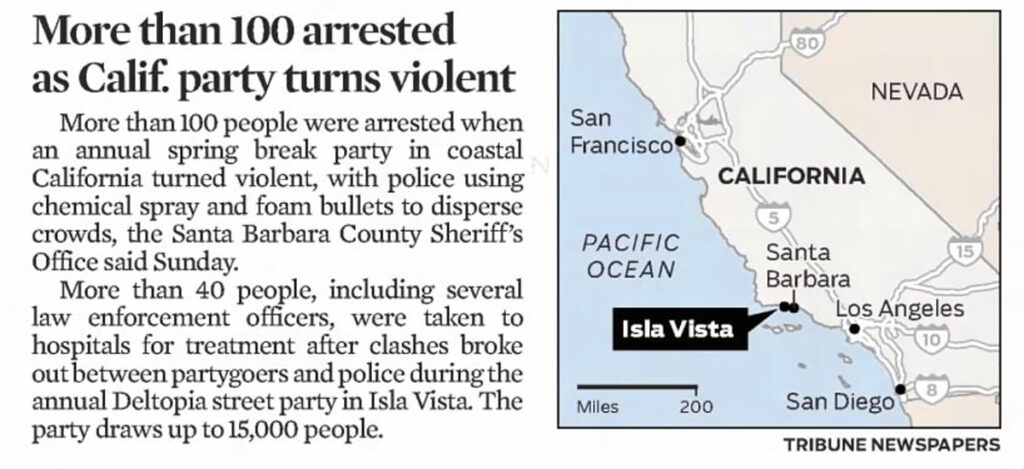

Isla Vista continues to occasionally make national news for all the wrong reasons. The attraction of a small beach town full of young people continues to draw crowds from all around the nation, often resulting in mayhem.

The local authorities continue to wrestle with controlling the latest Big Party, from Halloween to Deltopia, and they are usually outnumbered. UCSB being named the Best Party School, year in and year out, certainly doesn’t help.

Throngs of rowdy out of towners added to the terminal overpopulation of a town teetering on the edge of the Pacific, any number of things can go wrong. Especially when you add alcohol.

Isla Vista has been a constant in the author’s life. As a child in the 1960s, my mother forbade me from going “out there”. As a teenager, that’s where we scored beer. As a college student, it was party central. And as an adult, it is town I rarely visit. Pictured above- my future wife and I enjoying a free concert in the People’s Park.

When making this page, I paid a visit and saw that while there were more corporate chains than ever before, I.V. is essentially the same old town. Small, dirty, crowded and bustling with activity.

The Eucalyptus Curtain, planted by the Den brothers, is barely hanging in there.

The Welcome sign is looking a little tired….

We noticed at least one local business that has been there since the 1970s. Originally called Sip Our Suds Beer, it was the first place allowed to sell beer after the riots. Still going strong selling one of the essentials of college life.

It appears the future for Isla Vista will be more of the same since UCSB continues to increase their enrollment and ignore the housing problem they create. Most likely the next phase for development will be demolishing the old, cheaply made apartments and replacing them with new, taller, cheaply made apartments.

What would the Ilharreguys think of the result of their little plan for a seaside community? It was created out of a desire to make a profit, and surely thousands of investors have done just that. So in that respect, it was a success. But they had no way of knowing a major university would pop up right next door, drastically changing the course of history forever.

But Isla Vista is still a naturally beautiful place with a perfect climate, and nothing will ever change that.

PS- I could have made a whole page of just my own personal memories from I.V. We would love to hear your memories of Isla Vista, good or bad. Feel free to share them in the comments.

Tom – tMo! Thank you for another fine History lesson… Really appreciate the comment near the end: “Most likely the next phase for development will be demolishing the old, cheaply made apartments and replacing them with new, taller, cheaply made apartments.” calling like it is!

thanks.

This is one of the most interesting local stories I have read in years. So well done and informative. Thank you for all the hard work putting this together. Overcrowding and cliff erosion problems in IV seem to be eternal.

Great article, great photos. I remember Carmen Lodise knocking on my door (1972?), and inviting me to get involved. Then smashing a home run in a softball game a few years later (he was on the opposing team). Then in 1988, there was Carmen at an IVRP meeting, focusing the Board to oppose my proposed house on one of those skinny 25′ Del Playa lots. It’s the blue metal roof bowling alley at 6773 DP.

PS The article notes that lack of water hobbled IV development prior to Cachuma. Lack of water (plus a water moratorium) in 1972 also constrained IV growth. Some artful agreements resulted in a market for meters in the late 80’s. They were not cheap; $35K was the going rate.

I love the old Welcome sign! They should just fix it up and leave the design as it is. CLASSIC.

agreed!

Also, I never knew this about Rusty’s Pizza! Way cool.

Really really awesome Tom! Our community is better having your research and stories posted here. Thank you for taking the time to put these together.